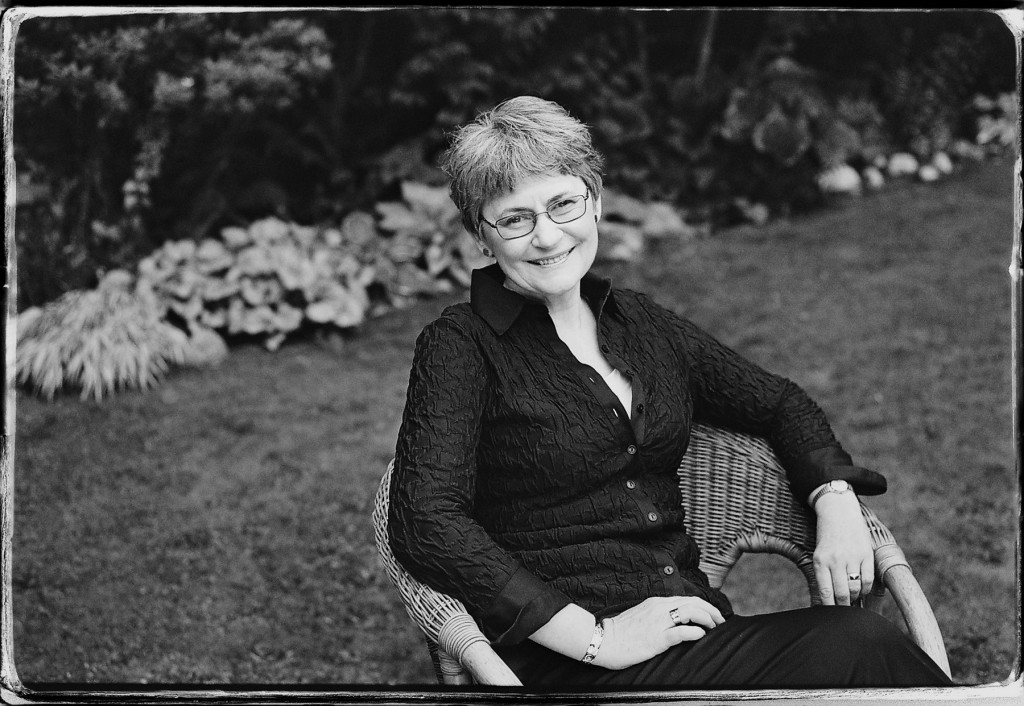

I recently connected with writer Mary Novik, author of the novel Conceit, on Twitter, and she graciously agreed to answer a few questions for me.

I noticed that the story of John Donne’s vision of Ann with a dead child appeared in the book. I tell this story to my students when we study “A Valediction: Forbidding Mourning.” What is one thing you wish your own English teacher had taught you about John Donne?

I would have loved to have known that, as a young man, John Donne sowed his wild oats with great abandon. Instead, my English instructors presented Donne as a devout husband and as a writer of holy sonnets. Sure, many of his best poems fall into those categories, but he also wrote seduction poems to women other than his wife, Ann. Knowing he was a bit of a lad rounds him out and makes him more intriguing. Although I’d admired his more sedate poems for years, it wasn’t until I discovered one of his racy elegies that I decided to write Conceit.

You have said you chose Pegge Donne because so little was known about her, so she aroused your curiosity. What do we know about her aside from Donne’s mention that she had the pox? For instance, were you able to find records for her family, such as the names of her children and grandchildren (the name Duodecimus kills me!)?

Donne only mentions his daughter Margaret in two letters, one about her baptism and one in which he announces “Pegge has the pox”. That was one of the triggering facts for Conceit. Smallpox could cause hair loss, scarring, and even death. My imagination ran riot. How would a fifteen-year-old in love with a family friend, the fisherman Izaak Walton, react to her hair falling out? Pegge’s personality began to take shape around this dramatic episode. Church and court documents only tell us the bare minimum about Pegge: her marriage, names of her children, her death. Duodecimus (which means “twelve”) was the real name she gave her youngest son. From that odd fact I came up with the idea that she was eccentric like her father and had twelve children like her mother. Did she identify with her mother? Did she read her father’s love poems? On it went, fact mingling with fiction, until I had my own Pegge, the main character of Conceit.

I enjoyed meeting up with the likes of Samuel Pepys and Christopher Wren in the novel. Some people might consider it coincidental, but I felt it showed the connectedness of humanity. In some ways, this book seemed to be about the ways in which we are all connected to one another and are important to one another—and it reminded me of Donne’s Meditation XVII in which he says, “No man is an island, entire of itself; every man is a piece of the continent, a part of the main. If a clod be washed away by the sea, Europe is the less, as well as if a promontory were, as well as if a manor of thy friend’s or of thine own were: any man’s death diminishes me, because I am involved in mankind, and therefore never send to know for whom the bells tolls; it tolls for thee.” I was wondering if you could discuss the influence of this work of Donne’s on the novel.

Meditation XVII is so powerful that people often think it’s poetry, but it’s actually one of the twenty-three prose meditations in Devotions, which Donne wrote when ill and in a spiritual crisis. He was an amazing prose stylist. Today we think of priests as rather stuffy, but Donne’s sermons (like “Death’s Duel”) have wild, obsessive imagery. I was very influenced by Donne’s writing when I was working on Conceit. It’s been called a woman’s novel but, looking at it now, I would agree it’s also a meditation about humanity and evolving personal relationships in the 17th century. Although most marriages are arranged, John Donne and Ann More are so feverishly in love they elope, sacrificing their worldly status. Later, Donne arranges safe marriages for his daughters, but Pegge’s turns out differently than expected. In Conceit, this dance between men and women is often narrated by men. Two of my favourite chapters are “Virtuoso,” in which Pepys aches with pity for his wife, and “Unbuttoning,” in which William struggles to understand Pegge and the mysteries of human love.

One of the things I admired about this book was the way you brought life in the seventeenth century into vivid relief. Many historical novels throw in a few trenchers, some stays, and an archaic word here and there, but otherwise have people walk and talk like we do. I didn’t forget for a moment that I was reading historical fiction because I felt immersed in another time. It also occurred to me that it must be difficult to capture another time period and yet still help the modern reader along. How do you think writing historical fiction like Conceit is different from other kinds of fiction?

When I was writing Conceit, I was totally immersed in the characters. I’ve visited London many times, but if Pegge is walking along a street, I try to show it through her eyes not mine. What has changed since she was last here? Where is she going, and why? I don’t want to gawk like a tourist at things Pegge won’t notice. Too much description of, say, the lack of hygiene will kick the modern reader out of the story. I want the reader to smell, hear, and taste as my character does. An example is the scene in which Pegge runs along Fleet street and counts the taverns she passes. I used the names of taverns that actually existed, but she’s just a kid, counting them off because she’s racing home, her gown flying, to hide in her bedchamber before her father discovers she’s been out late at night.

Do you have any advice for writers?

Start with something short, like stories! Send the stories out to periodicals. Take workshops. Form a writers’ group. If you decide you absolutely have to write a novel, be prepared to throw everything at it, time, money, energy, for about five years. Do it only if you absolutely must. Don’t rush. Don’t try to figure out everything in advance or take the most straightforward path. And don’t just tell the story: let your characters talk to one another and reveal it for you. When that happens, you’ll know they have come alive on the page, full of passion and surprise. That’s the most glorious feeling.

Thank you very much, Mary!

You can read my review of Conceit here. You can follow Mary Novik on Twitter, and be sure to check out her website.