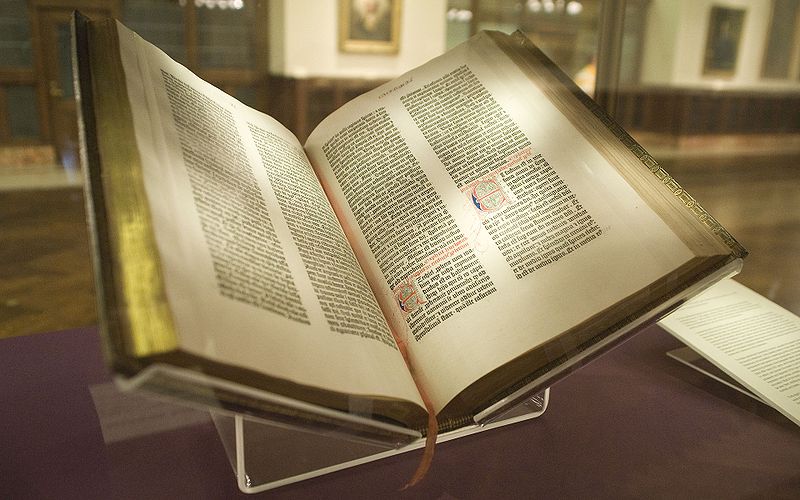

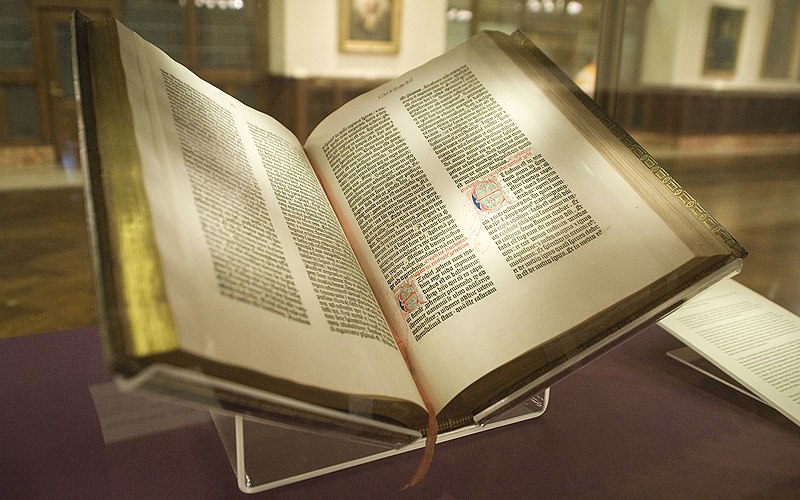

Did you know that it was today in 1456 that the printing of the Gutenberg Bible was completed? It was the first major book printed using the movable type printing press. Twenty-one complete copies survive, but other incomplete copies remain. Font nerds might be interested to know that Gutenberg used typefaces called Textualis and Schwabacher. Textualis is sometimes just called Gothic now. The columns were also justified, which you can see from the photograph. Of course, justified columns are still used today in books and newspapers. It was an instant bestseller, selling out of its initial print run of 180 copies. Interestingly, many buyers purchased the Bibles in order to donate them to religious institutions. I’m sure they thought that would be a check in the “nice” column for when they met St. Peter at the pearly gates. One of my own ancestors, David Kennedy, appears to have donated a Bible (not a Gutenberg, of course) to his church with a similar motivation. Germany possesses the most remaining copies at 12, but you can find 11 copies in the United States and 8 in the United Kingdom. The Library of Congress, Pierpont Morgan Library, Yale, Harvard, and the University of Texas at Austin have complete copies. I might have guessed Harvard and Yale would have the kind of endowments necessary to own a complete Gutenberg Bible, but I was surprised at UT Austin. They apparently acquired their Gutenberg in 1978 from the Carl H. Pforzheimer Foundation. The first volume has been illuminated by a former owner about which we know nothing. It also bears annotations that indicate it has been owned and loved. I adore the fact that some annotations are corrections. I correct errors in books sometimes, too.

Did you know that it was today in 1456 that the printing of the Gutenberg Bible was completed? It was the first major book printed using the movable type printing press. Twenty-one complete copies survive, but other incomplete copies remain. Font nerds might be interested to know that Gutenberg used typefaces called Textualis and Schwabacher. Textualis is sometimes just called Gothic now. The columns were also justified, which you can see from the photograph. Of course, justified columns are still used today in books and newspapers. It was an instant bestseller, selling out of its initial print run of 180 copies. Interestingly, many buyers purchased the Bibles in order to donate them to religious institutions. I’m sure they thought that would be a check in the “nice” column for when they met St. Peter at the pearly gates. One of my own ancestors, David Kennedy, appears to have donated a Bible (not a Gutenberg, of course) to his church with a similar motivation. Germany possesses the most remaining copies at 12, but you can find 11 copies in the United States and 8 in the United Kingdom. The Library of Congress, Pierpont Morgan Library, Yale, Harvard, and the University of Texas at Austin have complete copies. I might have guessed Harvard and Yale would have the kind of endowments necessary to own a complete Gutenberg Bible, but I was surprised at UT Austin. They apparently acquired their Gutenberg in 1978 from the Carl H. Pforzheimer Foundation. The first volume has been illuminated by a former owner about which we know nothing. It also bears annotations that indicate it has been owned and loved. I adore the fact that some annotations are corrections. I correct errors in books sometimes, too.

In completely unrelated news, I am putting The Lost Memoirs of Jane Austen on hold to read The Hunger Games. Not one person I know has had anything less than absolute and unequivocal praise for Suzanne Collins’s trilogy. I need to see what the fuss is all about.

In completely unrelated news, I am putting The Lost Memoirs of Jane Austen on hold to read The Hunger Games. Not one person I know has had anything less than absolute and unequivocal praise for Suzanne Collins’s trilogy. I need to see what the fuss is all about.

Also, Amazon sent me an email today suggesting I might be interested in Juliet by Anne Fortier, and I am. Check out the Publisher’s Weekly blurb:

Also, Amazon sent me an email today suggesting I might be interested in Juliet by Anne Fortier, and I am. Check out the Publisher’s Weekly blurb:

Fortier bobs and weaves between Shakespearean tragedy and popular romance for a high-flying debut in which American Julie Jacobs travels to Siena in search of her Italian heritage—and possibly an inheritance—only to discover she is descended from 14th-century Giulietta Tomei, whose love for Romeo defied their feuding families and inspired Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet. Julie’s hunt leads her to the families’ descendants, still living in Siena, still feuding, and still struggling under the curse of the friar who wished a plague on both their houses. Julie’s unraveling of the past is assisted by a Felliniesque contessa and the contessa’s handsome nephew, and complicated by mobsters, police, and a mysterious motorcyclist. To understand what happened centuries ago, in the previous generation, and all around her, Julie relies on relics: a painting, a journal, a dagger, a ring. Readers enjoy the additional benefit of antique texts alternating with contemporary narratives, written in the language of modern romance and enlivened by brisk storytelling. Fortier navigates around false clues and twists, resulting in a dense, heavily plotted love story that reads like a Da Vinci Code for the smart modern woman.

So who took liberties? Shakespeare or Fortier? It was no friar who wished a plague on both house (it was Mercutio). How did Juliet have descendants? And why Siena instead of fair Verona? Still, I am intrigued. And it was probably Shakespeare.

Photo credit Kevin Eng.