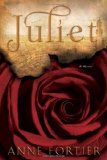

After the death of her Aunt Rose, Julie Jacobs is given an intriguing bequest—a key to a safety deposit box in a bank in Siena, Italy. As keys do, this key unlocks the door to a future Julie could never have imagined as she discovers her connection to the star-crossed lovers who inspired William Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet.

After the death of her Aunt Rose, Julie Jacobs is given an intriguing bequest—a key to a safety deposit box in a bank in Siena, Italy. As keys do, this key unlocks the door to a future Julie could never have imagined as she discovers her connection to the star-crossed lovers who inspired William Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet.

Juliet is a fast-paced thriller that fans of William Shakespeare’s play will enjoy. Fortier weaves in references to Romeo and Juliet both obvious and subtle. The ending probably won’t surprise readers much, but the ride is a great deal of fun. Fortier’s research is meticulous. She brings Siena alive, both in the medieval past and present. She introduces the Tolomeis and Salimbenis, two prominent Siena families who really did have a feud. Reading this book made me want to teach Romeo and Juliet again this year, and here I thought I was a little tired of it.

I was puzzled by Fortier’s choice of Siena, when it is in fair Verona that Shakespeare lays his scene, but after doing some digging, I found the earliest references to a story involving Romeo and Juliet set the story in Siena, and Siena makes a great deal of sense with its history of feuding families and its ancient traditions, including the Palio, a horse race that originated in the Middle Ages. A sense of the connection we all have to history pervades this book. My interest in family history and in medieval history made this an enjoyable read. You’ll read reviews that compare this novel to The Da Vinci Code, which I suppose is inevitable because of the unraveling of clues bound to reveal surprising information that will upend long-held beliefs against the backdrop of a European city, but don’t let the comparisons fool you. This novel is much smarter than The Da Vinci Code, and the characters are much more fully realized. I did feel Julie’s sister Janice could be a bit of a caricature, and Eva Maria was a little over the top, but I enjoyed the other characters, especially the characters in the medieval portions of the story—Giulietta Tolomei, Romeo Marescotti, Friar Lorenzo, and the feuding Tolomeis and Salimbenis.

Anyone who enjoys Shakespeare-related fiction should enjoy this novel, but even folks who aren’t Shakespeare fans can enjoy this read.

Rating: