The Complete Sherlock Holmes by Arthur Conan Doyle

The Complete Sherlock Holmes by Arthur Conan Doyle Pages: 1796

Buy on Amazon

Goodreads

Ever since he made his first appearance in A Study In Scarlet, Sherlock Holmes has enthralled and delighted millions of fans throughout the world.

In January 2017, I undertook a reading challenge to read all the Sherlock Holmes stories by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle: all 56 short stories and four novels. The idea behind the Chronological Sherlock Holmes Challenge is to read the stories in the order in which they are set. I have had some quibbles with the exact order of these stories established in the chronology the challenge used, and it’s likely that disagreement regarding the exact chronology exists, though I admit I haven’t delved much into the matter. In any case, chronologically is not how Conan Doyle published them, and I wonder if something is lost when attempting to order them by the time setting rather than reading them as Conan Doyle collected them.

Of the collected stories, here is my personal top ten:

- The Hound of the Baskervilles: I love the atmosphere in this one. It seems to capture some of the best aspects of the Sherlock Holmes stories, and it is easily far and away the best of the four novels (the other three aren’t very good, in my opinion, as two are set partly in America, a place which Conan Doyle does not understand, and the other, while introducing Mary Morstan and having some good moments, is pretty racist).

- ” Scandal in Bohemia”: One likes to imagine Holmes was in love with Irene Adler, but he mostly presents as asexual. I like this one because it is one of the few stories in which a woman is a strong character. The Sherlock episode “A Scandal in Belgravia” was one of the best.

- “The Adventure of the Yellow Face”: I liked this one for two reasons, 1) Holmes didn’t figure it out and came away with egg on his face, and 2) Conan Doyle wasn’t typically racist. If I noticed one theme over and over, it’s that the white English characters find themselves to be superior to all other people in the world, and South Americans, Asians, and Africans are frequently described as barbaric in comparison. I am not a fan of that racist stereotyping, even in Victorian/Edwardian writing. The only problem with this one is its premise falls apart if you know that anti-miscegenation laws would have prevented the marriage at the heart of the mystery.

- “The Adventure of the Bruce-Partington Plans”: I liked this one for the setup and masterful way Holmes deduced what happened. The Sherlock episode based on it was great. Also, Mycroft!

- “The Adventure of the Final Problem”: Who can forget Homes and Moriarty going over the Reichenbach Falls?

- “The Five Orange Pips”: A famous one in which Holmes does not prevent his client’s death. Not so sure I buy the KKK angle, but I liked the setting.

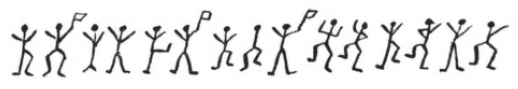

- “The Adventure of the Dancing Men”: I liked this one for the codes. It was fun to see Holmes turn cryptographer.

- “The Adventure of the Copper Beeches”: This is one of several governess stories, but I liked it the best of that lot.

- “The Man with the Twisted Lip”: I liked the opium den. So seedy.

- “The Adventure of Silver Blaze”: This one is a good setup for the reader as an amateur sleuth. There are red herrings and the reference from which the title of Mark Haddon’s The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time is drawn.

The order is a bit arbitrary, particularly at the end. Something I have noticed about my own preferences is that I seem to like the stories when Holmes and Watson pack up for the countryside best. Not sure why because I also like the setting of 221B Baker Street. Re-reading the stories also demonstrated (at least to me) how clever the BBC Sherlock series is. They do a brilliant job showing the timelessness of the stories, adapting them for a modern era. They seem to approach capturing the character of Sherlock Holmes better than just about any other adaptations I’ve seen. Holmes can be arrogant, annoying, dismissive (especially of Watson), and those characteristics shine through most in Benedict Cumberbatch’s representation of the character.

And what a character. No wonder we are still reading these stories. Conan Doyle’s detective is the model for every detective character who has followed him. He’s the kind of character most writers would see as a gift. I understand Conan Doyle felt his Sherlock Holmes stories “stood in the way of the recognition of my more serious literary work.” That did happen. Because whatever that other stuff was, no one is reading it today. It is the character of Sherlock Holmes who ultimately established Conan Doyle’s legacy as a writer. One could do much, much worse.

Some passages in the stories move well past utilitarian and reveal Conan Doyle to be a skilled writer at the sentence level. In “His Last Bow,” The final story I read for the challenge and a tale in which Holmes foils the plans of a German spy by posing as one himself, thereby aiding in the war effort, these sentences: “One might have thought already that God’s curse hung heavy over a degenerate world, for there was an awesome hush and a feeling of vague expectancy in the sultry and stagnant air. The sun had long set, but one blood-red gash like an open would lay low in the distant west.” However, I admit that I didn’t care much for that story by the end. It smacked of inserting Holmes into World War I in a weird way. It’s not that it was implausible, but it was sort of like Conan Doyle was looking for an excuse to let Holmes fight the Germans and rescue the British. Not that he completely does: it is open-ended, with Holmes musing that “There’s an east wind coming, Watson.” Later, he adds, “such a wind never blew on England yet. It will be cold and bitter, Watson, and a good many of us may wither before its blast. But it’s God’s own wind none the less, and a cleaner, better, stronger land will lie in the sunshine when the storm has cleared.” I admit to a feeling of wistfulness when Holmes draws Watson to “Stand with me here upon the terrace, for it may be the last quiet talk we shall ever have.”

The stories are often funny, as well, which is something BBC’s Sherlock also captures. Here are my top ten Sherlock quips:

- “Cut the poetry, Watson,” said Holmes severely. “I note that it was a high brick wall.” (“The Adventure of the Retired Colourman”)

- “Detection is, or ought to be, an exact science and should be treated in the same cold and unemotional manner. You have attempted to tinge it with romanticism, which produces much the same effect as if you worked a love-story or an elopement into the fifth proposition of Euclid.” (The Sign of Four)

- “We have got to the deductions and inferences,” said Lestrade, winking at me. “I find it hard enough to tackle facts, Holmes, without flying away after theories and fancies,” “You are right,” said Holmes demurely; “you do find it very hard to tackle the facts.” (“The Boscombe Valley Mystery”)

- “And a singularly consistent investigation you have made, my dear Watson,” said he. “I cannot at the moment recall any possible blunder which you have omitted. The total effect of your proceeding has been to give the alarm everywhere and yet to discover nothing.” (“The Disappearance of Lady Frances Carfax”)

- “I read nothing except the criminal news and the agony column. The latter is always instructive.” (“The Adventure of the Noble Bachelor”)

- “He can find something,” remarked Holmes shrugging his shoulders; “he has occasional glimmerings of reason.” (The Sign of Four)

- “I knew my man, however, and I clapped a pistol to his head before he could strike. Then he became a little more reasonable.” (“The Adventure of the Beryl Coronet”)

- “By George!” cried the inspector. “How ever did you see that?” “Because I looked for it.” (“The Adventure of the Dancing Men”)

- “But there are always some lunatics about. It would be a dull world without them.” (“The Adventure of the Three Gables”)

- “I don’t take much stock of detectives in novels—chaps that do things and never let you see how they do them. That’s just inspiration: not business.” (The Valley of Fear)

Watson has a fair few good ones, too:

- “You would certainly have been burned, had you lived a few centuries ago.” (“A Scandal in Bohemia”)

- I believe that I am one of the most long-suffering of mortals; but I’ll admit that I was annoyed at the sardonic interruption. “Really, Holmes,” I said severely, “you are a little trying at times.” (The Valley of Fear)

- “I must admit, Watson, that you have some power of selection, which atones for much which I deplore in your narratives. Your fatal habit of looking at everything from the point of view of a story instead of as a scientific exercise has ruined what might have been an instructive and even classical series of demonstrations. You slur over work of the utmost finesse and delicacy, in order to dwell upon sensational details which may excite, but cannot possibly instruct, the reader.” “Why do you not write them yourself?” I said, with some bitterness. (“The Adventure of the Abbey Grange”)

- [T]he page had shown in a tall, clean-shaven man with the firm, austere expression which is only seen upon those who have to control horses or boys. (“The Adventure of Shoscombe Old Place”)

- He was none the less in his personal habits one of the most untidy men that ever drove a fellow lodger to distraction. (“The Musgrave Ritual”)

I have now read all 60 stories in Chronological Sherlock Holmes Challenge.

I have now read all 60 stories in Chronological Sherlock Holmes Challenge.

This challenge was enjoyable if for no other reason than it gave me an excuse to re-read all the stories. It had been quite a long time since I had done so.

If I re-read this series again, I think I’ll try it audio, and I will skip the stories I liked less. I will also not try to read it chronologically again. I think it was an interesting experiment, but Conan Doyle was a bit too sloppy with his timelines to make it work. Watson’s marriage was the most confusing aspect of the timeline. What Conan Doyle needed was some kind of spreadsheet to track events. In any case, it reminds me a bit of the inconsistency in J. K. Rowling’s books. One thing I definitely want to do whenever I finally get to visit London is see the site of Sherlock Holmes’s lodgings at 221B Baker Street, though I understand the Abbey National Building Society is on the real site of the address, while the Sherlock Holmes Museum, which has a blue plaque claiming it is at 221B Baker Street, is actually between 237 and 241 Baker Street.

Olive Kitteridge by

Olive Kitteridge by

Selected Letters by

Selected Letters by

How It Went Down by

How It Went Down by

1984 by

1984 by