It’s my favorite time of year again. Fall, and the R. I. P. Challenge! I am late signing up because I didn’t realize that the challenge had permanently been transferred to Estella’s Revenge. You can access the sign-up post through this link.

It’s my favorite time of year again. Fall, and the R. I. P. Challenge! I am late signing up because I didn’t realize that the challenge had permanently been transferred to Estella’s Revenge. You can access the sign-up post through this link.

I don’t really know what I want to read yet. I have a few ideas, as I have been thinking about books for the challenge, but as usual, I don’t really want to commit to titles because I like the flexibility of grabbing something that interests me.

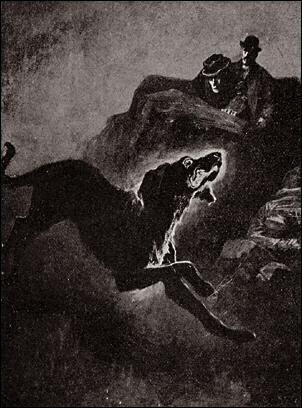

I am going, as usual, with Peril the First: “Read four books, any length, that you feel fit (our very broad definitions) of R. I. P. literature. It could be Stephen King or Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, Shirley Jackson or Tananarive Due … or anyone in between.”

I don’t believe I will participate in the group read.

Who is with me?