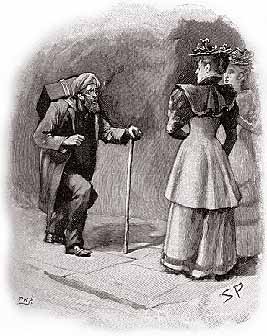

“The Adventure of the Crooked Man” begins with a late-night visit by Sherlock Holmes to Watson’s new home, a short time after Watson’s marriage. Holmes wants to take Watson on an adventure the following morning and after making a few (kind of annoying, to be honest) deductions about Watson’s smoking habits, home repairs, and lack of visitors, he settles down with a pipe and tells Watson the particulars of the case, which involves the death of James Barclay shortly after a verbal altercation with his wife. Mrs. Barclay is suspected of his death, but Holmes isn’t so sure. He has deduced there was a third party in the room—a third party, moreover, who had a mysterious animal Holmes can’t identify with him. He invites Watson to skive off doctoring and escort him to Aldershot to investigate the case further, and Watson readily accepts.

I am at a loss to explain why this story is in the twelfth position chronologically, as Watson is married, and we haven’t even met Mary Morstan yet in our chronological reading. I’ll keep going with the chronology as posted (and it is no conjecture of the challenge host, but rather that of Brad Keefauver of Sherlock Peoria), but this is the second time I’ve noticed a reference to Watson having married already and no introduction yet to Mary. In fact, I just don’t think this story takes place in 1887. That would be the earliest date for the story, but it doesn’t work out in other ways. It’s likely set a couple of years later.

Some fun trivia: Holmes never says his famous line, “Elementary, my dear Watson” in any actual story, but he comes fairly close in this one when, after Watson praises Holmes’s deduction as “Excellent!,” he tells Watson it was “Elementary.” Another interesting bit of trivia: this story has one of the few examples of biblical allusion I’ve seen in the stories. I’ll keep my eyes peeled for more, but Sherlock surprised me by deducing this allusion Nancy Barclay made while fighting with her husband.

Why wouldn’t Holmes know what a mongoose is? That is a question I still have after reading this story. He seems to have encyclopedic knowledge in a variety of fields. One would think he would have at least have heard of the mongoose, but Henry Wood’s explanation of what a mongoose is seems to be necessary, so it stands to reason Holmes has no idea what they are. This story is set before Kipling wrote “Rikki-Tikki-Tavi,” but I should still think Holmes would have heard of them at least. And if not Holmes, why not Watson? I looked into it, and while they are not widespread in Afghanistan, they do live in the southern part. Would Watson never have heard of them while serving in the military in Afghanistan? I suppose it’s possible. I don’t know why I have such a mental block around believing Holmes and Watson are both completely unfamiliar with the mongoose. It’s probably just me.

I found no references in the Sherlock series to this story, either, and in my humble opinion, it’s a bit of a throwaway. For one thing, Holmes has just about solved the entire case before he ever visits Watson. Spoiler alert ahead: Holmes isn’t really investigating a murder after all, and as such, the case doesn’t really have anywhere to go. I suppose Holmes does make the correct deduction about the events involved, but it’s mostly Holmes and then Henry Wood who tell the story through exposition. It was interesting enough, but it doesn’t rank up near the top in memorable Sherlock Holmes stories for me, and once again, it contains some troubling racist attitudes among some of the characters. I suppose we are meant to give Conan-Doyle a pass because of the times, but he showed some remarkably different thinking in “The Yellow Face,” so I don’t know that he gets a pass regarding his depictions of Indians, even if that depiction matched the prevailing attitude of Britons at the time the story was written and in which it was set.

Rating:

I read this story as part of the Chronological Sherlock Holmes Challenge. It is the twelfth story in the chronology (time setting rather than composition). Next up is “The Five Orange Pips.”

I read this story as part of the Chronological Sherlock Holmes Challenge. It is the twelfth story in the chronology (time setting rather than composition). Next up is “The Five Orange Pips.”