After finishing “The Engineer’s Thumb” and “The Cardboard Box,” I am caught up on the Chronological Sherlock Holmes Challenge. It’s strange that these two stories would fall one after the other in the chronology as both feature grisly dismembered appendages.

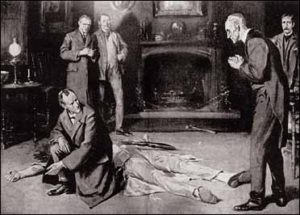

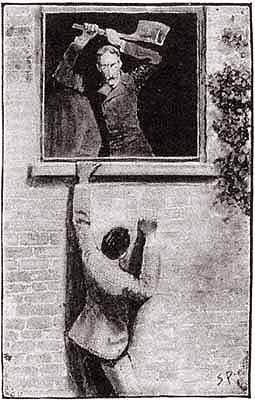

“The Engineer’s Thumb” is unique in that Watson first encounters a mystery that he brings to Sherlock Holmes rather than the other way around, which is more typical. Watson receives a patient whose thumb has been severed—the patient says purposely and with murderous intent—and he takes Victor Hatherley, the unfortunate engineer of the title, to Sherlock Holmes so that his friend can look into the man’s case. Hatherley recounts his story to Holmes, and it is clear the man was lucky to escape with his life after discovering an illegal counterfeit operation. This story is unique also in that Holmes does not bring the criminals to justice, as the remote house where they carried out their operation has burned and they have escaped.

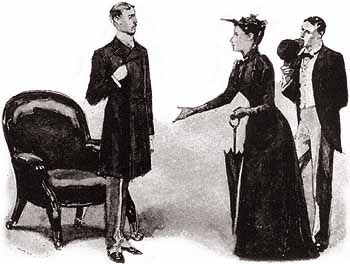

In “The Cardboard Box,” Holmes is consulted because a woman named Susan Cushing has received a mysterious package addressed to “S. Cushing” containing two ears, and she can’t imagine why on earth anyone would send her such a ghastly package unless it is a couple of disgruntled former boarders who happened to be medical students. Holmes deduces that the package was not meant for the Susan, but for her sister Sarah, who until recently lived with the woman. He also deduces that one of the ears belongs to a third sister Mary, based on its similarity to those of Susan. With a few quick deductions, he nabs the culprit, who confesses all.

Both of these stories are a bit more grisly than is typical for Sherlock Holmes stories, and both contain surprises, but I wouldn’t rate either among the best I’ve read. The BBC Sherlock series doesn’t allude to either story that I can recall. Also, it appears that Conan Doyle has mixed up his chronology, as Watson is living at Baker Street during “The Cardboard Box,” supposedly after he has married Mary. I’m not going to theorize that there was trouble in the Watson marriage. Looks like a simple goof to me.

“The Cardboard Box” does have an interesting and introspective ending, furnished by Sherlock Holmes:

“What is the meaning of it, Watson?” said Holmes solemnly as he laid down the paper. “What object is served by this circle of misery and violence and fear? It must tend to some end, or else our universe is ruled by chance, which is unthinkable. But what end? There is the great standing perennial problem to which human reason is as far from an answer as ever.”

“The Engineer’s Thumb” Rating:

“The Cardboard Box” Rating:

I read these stories as part of the Chronological Sherlock Holmes Challenge. They are the twenty-fourth and twenty-fifth stories in the chronology (time setting rather than composition). Next up is the final novel in the chronology, The Hound of the Baskervilles.

I read these stories as part of the Chronological Sherlock Holmes Challenge. They are the twenty-fourth and twenty-fifth stories in the chronology (time setting rather than composition). Next up is the final novel in the chronology, The Hound of the Baskervilles.