This review might be a bit spoilery if you haven’t read the first book in this series because it’s difficult to talk about events in this book without revealing the end of the first.

This review might be a bit spoilery if you haven’t read the first book in this series because it’s difficult to talk about events in this book without revealing the end of the first.

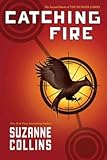

Suzanne Collins’s second book in The Hunger Games trilogy, Catching Fire, picks up the story of Katniss Everdeen after she and fellow District 12 resident have become popular winners of the 74th Hunger Games. Katniss and Peeta must tour the districts, where they are greeted with signs of unrest—and Katniss seems to have become an unwitting rallying point for rebels. President Snow, loathsome leader of Panem, blames these new problems on Katniss’s defiance of the Capitol at the Games when she threatened to kill herself rather than kill Peeta. For the 75th Hunger Games, the 3rd Quarter Quell, President Snow has something special in mind. The pool of competitors will be drawn from each district’s former winners. And Katniss is the only female winner from District 12. She will have to go back into the arena, and this time, she will be facing her most dangerous competitors: people who have managed through shrewdness and strength to win the Hunger Games in the past. How can she hope to survive her second turn in the arena? And if she can’t, how can she at least protect Peeta?

I had heard some readers say this book was not as good as the first, but I have to admit I didn’t see it. Others had complained that the first half was somewhat slow, but I managed to turn the pages as quickly as I had with The Hunger Games. It was intriguing to me to see how Katniss handled being a victor, seeing her life change. I also found the changes in her district interesting. Katniss is not the kind of girl to sit idly by and do nothing if anyone she cares about is being hurt. Because the real news about what is going on in Panem is kept from the districts, it’s only by accident—seeing a news program meant for District 12’s mayor and running into some escapees from District 8 in the woods while she is hunting—that Katniss realizes her act of defiance in the Hunger Games has turned her into a symbol for rebellion. On her district tour, she witnesses some of the unrest for herself. Seeing Katniss compete in the arena this time, with new threats devised by the Gamemakers, had me turning the pages well past 2:00 or 3:00 in the morning. One of my students said in class on Friday that the end of this volume of the trilogy was “epic,” and I would agree. So much happens so fast at the end, and as we readers are following events from Katniss’s confused perspective, it’s difficult to figure out what is going on. I was also right about some speculation I had while reading The Hunger Games, but it’s a pretty spoilery if you haven’t read the first book or even the second.

I told my dad the other day that I had just read the new Harry Potter after I’d finished The Hunger Games. I really don’t think these books will reach that level of popularity, and maybe won’t reach even the level of the Twilight series, which is a shame because despite their darkness, I think they’re better. What I meant was I had found a new book that had me turning the pages in the exact same way as the Harry Potter series. Virtually everyone I know is reading these books or has just finished them.

Suzanne Collins is on a twelve-city book tour to promote Mockingjay, but she isn’t venturing into the South. Unfortunately, she has strained her hand and will not be signing books on her tour. I have wondered a couple of times as I read what Collins makes of the books’ popularity. I purchased my copy of Mockingjay at the Little Shop of Stories yesterday while we were at the Decatur Book Festival. Now I just have to resist reading it for a little while as I try to get to work on my portfolio for graduate school.

Rating:

Full disclosure: I borrowed this book from my friend Catherine.