I know it’s Friday. Stop giving me the shifty eye. It was a hectic week. Sick children, missing Girl Scout sash, AP Information Night at the high school. I really like this week’s Booking Through Thursday prompt: Which authors have you been lucky enough to discover at the very beginning of their careers? And which ones do you wish you’d discovered early? I needed some time to think about it. I am not often the person who discovers a new author after his/her first novel, but I did get in on the ground floor, so to speak, with both Matthew Pearl and Katherine Howe. I read Matthew Pearl’s first novel The Dante Club probably when it had been released in paperback. He found a blog post directed to my students recommending the book and invited me to a reading/signing at the Decatur Library here in the Atlanta area for his new book—The Poe Shadow. It was great to meet him and have him remember that I was the “Ms. Huff” who mentioned his book to my students.

I was browsing at Borders and Katherine Howe’s first novel The Physick Book of Deliverance Dane caught my eye because it has a gorgeous cover. I saw that Matthew Pearl had written a blurb for it, and I grabbed it. Eye-catching cover, Matthew Pearl liked it—how could it not be good? And I truly did enjoy it. I have met Katherine, and she’s very friendly both in person and on Twitter.

I also read Kathleen Kent’s novel The Heretic’s Daughter after seeing it everywhere in Salem last summer. She has a new novel out called The Wolves of Andover. Kathleen Kent is a great example of how mining a fascinating family history can reap great rewards. I met her at the NCTE Conference in Orlando in November, and she was very friendly.

I was really lucky to discover Brunonia Barry early. I had an ARC of The Lace Reader and was able to read it before a lot of other folks did, although she had also previously published it with a smaller press. Those folks that read the very first edition must feel like they truly discovered her and that people like me are just posers.

What’s cool about all three is feeling like I haven’t missed out—and I’ve picked up all of their other works (except Katherine’s—she’s still working on her second).

You know, I’m such an English teacher nerd that most of the folks I wish I had discovered early are dead. For instance, William Shakespeare. How cool would it have been to go to the first production of the first play he wrote? Or the Beowulf author and Pearl Poet. Just to find out who they were. Or Shelley and Byron and Keats (oh my!). Or Oscar Wilde?

Psst. If you are so inclined, you could get in on the ground floor with me. I have one complete novel, a second that needs editing, and a third that isn’t finished yet. You can check out my novel here and see if it looks like something you’d like to read.

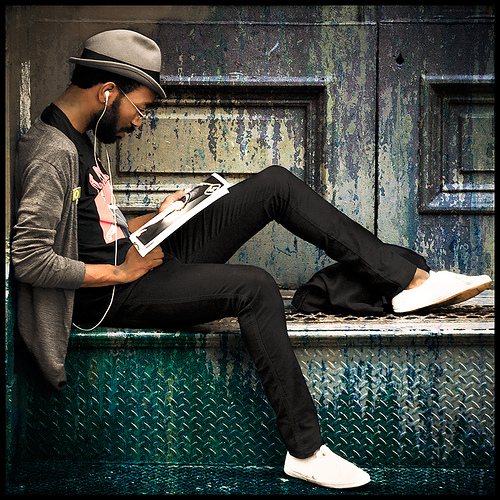

photo credit: bogenfreund

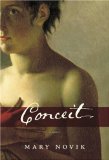

How much am I enjoying Jude Morgan’s novel

How much am I enjoying Jude Morgan’s novel