After reading last week’s story “The Adventure of the Noble Bachelor,” I am all caught up on the Chronological Sherlock Holmes Challenge.

Sherlock Holmes receives a fancy-looking note from Lord Robert St. Simon, the son of the Duke of Balmoral. The nobleman’s curious marriage had recently been the subject of the gossip columns. The bride would be bringing a great deal of American money into the old (but cash-strapped) family. However, she appears to have disappeared without a trace right after the wedding, in the middle of the wedding breakfast. A dancer, likely a former dalliance of Lord St. Simon’s, is Lestrade’s main suspect. He believes the other woman led the bride out under false pretenses and has perhaps murdered her rival. Sherlock Holmes is positive the story is quite different, and he claims to have solved it as soon as his interview with Lord St. Simon has ended.

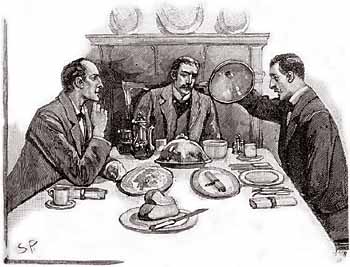

This story is one of the ones I have a quibble with because the deductions feel like cheats. The reader doesn’t have enough clues to reach the same conclusions as Holmes has, so his deductions appear to be based on other information not shared in the story. I don’t like it when Conan Doyle does this. Yes, it’s all very impressive how smart Holmes is, but Conan Doyle’s writing is at its best when he carefully lays clues that the reader might also string together. I’m complaining chiefly here about Holmes’s deduction on seeing the card with the note and initials and the hotel receipt that Lestrade shows Holmes. The reader is right with Holmes when he makes deductions about the identity of the man in the pew at the wedding and the comment the bride makes about “jumping a claim.” But how we could be expected to know the significance of the bill and the initials, I’m not sure. The character of Lord St. Simon is so odious, I’m glad he doesn’t get his way. He obviously married Hatty Doran only for her money, and their marriage wasn’t likely to be happy. I would have lain odds he’d have been back in the arms of his dancer before long. Hatty wouldn’t have been happy. The story does have some witty moments—the kinds of exchanges between Holmes and Watson, and also between Holmes and Lestrade, that make the BBC Sherlock series so much fun. Until going back to the stories for this challenge, I hadn’t remembered how much of the humor in that series is right here in the source material. Some choice excerpts:

“Here is a fashionable epistle,” I remarked as I entered. “Your morning letters, if I remember right, were from a fish-monger and a tide-waiter.”

“Yes, my correspondence has certainly the charm of variety,” he answered, smiling, “and the humbler are usually the more interesting. This looks like one of those unwelcome social summonses which call upon a man either to be bored or to lie.”

And this:

“I read nothing [in the newspapers] except the criminal news and the agony column. The latter is is always instructive.” (Sherlock Holmes)

I do not believe I recall any references to this story in the BBC series Sherlock, but in looking it up, I did learn about a couple of “mistakes” in the story. Lord St. Simon’s wife is referred to as “Lady St. Simon” in the story, which is apparently not correct. As the wife of the second son of the Duke (and therefore not his heir), the proper title should be “Lady Robert.” Likewise. “Lord St. Simon” should be “Lord Robert.” While one wouldn’t necessarily expect an American reader like me to get these nuances, it seems surprising that Conan Doyle would make such an error. Also, the description of Watson’s wound doesn’t match its description in A Study in Scarlet, where it was described as a wound in his shoulder: “I was struck on the shoulder by a Jezail bullet, which shattered the bone and grazed the sublavian artery.” In this story, Watson says, “I had remained indoors all day, for the weather had taken a sudden turn to rain, with high autumnal winds, and the jezail bullet which I had brought back in one of my limbs as a relic of my Afghan campaign, throbbed with dull persistency.”

I liked the characterization in this one, but not as much the story, and once again, Conan Doyle reveals a middling understanding of Americans at best. The dialogue he gives poor Hatty is dreadful. Not one of his best, but not terrible either.

Rating:

I read this story as part of the Chronological Sherlock Holmes Challenge. It is fourteenth story in the chronology (time setting rather than composition). Next up is The Valley of Fear, the second novel in the challenge.

I read this story as part of the Chronological Sherlock Holmes Challenge. It is fourteenth story in the chronology (time setting rather than composition). Next up is The Valley of Fear, the second novel in the challenge.