I finished several books, and with the busy end-of-school-year, I haven’t had a chance to share my thoughts about them.

Dust Child by Nguyễn Phan Quế Mai

Dust Child by Nguyễn Phan Quế Mai Narrator: Quyen Ngo

Published by Algonquin Books on March 14, 2023

Genres: Historical Fiction

Length: 12 hours 28 minutes

Format: Audio, Audiobook

Source: Library

Buy on Amazon, Buy on Bookshop

This post contains affiliate links you can use to purchase the book. If you buy the book using that link, I will receive a small commission from the sale.

Goodreads

From the internationally bestselling author of The Mountains Sing, a suspenseful and moving saga about family secrets, hidden trauma, and the overriding power of forgiveness, set during the war and in present-day Việt Nam.

In 1969, sisters Trang and Quỳnh, desperate to help their parents pay off debts, leave their rural village and become “bar girls” in Sài Gòn, drinking, flirting (and more) with American GIs in return for money. As the war moves closer to the city, the once-innocent Trang gets swept up in an irresistible romance with a young and charming American helicopter pilot, Dan. Decades later, Dan returns to Việt Nam with his wife, Linda, hoping to find a way to heal from his PTSD and, unbeknownst to her, reckon with secrets from his past.

At the same time, Phong—the son of a Black American soldier and a Vietnamese woman—embarks on a search to find both his parents and a way out of Việt Nam. Abandoned in front of an orphanage, Phong grew up being called “the dust of life,” “Black American imperialist,” and “child of the enemy,” and he dreams of a better life for himself and his family in the U.S.

Past and present converge as these characters come together to confront decisions made during a time of war—decisions that force them to look deep within and find common ground across race, generation, culture, and language. Suspenseful, poetic, and perfect for readers of Min Jin Lee’s Pachinko or Yaa Gyasi’s Homegoing, Dust Child tells an unforgettable and immersive story of how those who inherited tragedy can redefine their destinies through love, hard-earned wisdom, compassion, courage, and joy.

I really enjoyed The Mountains Sing, so I felt I’d enjoy Dust Child, and I was not wrong. I am not sure that comparisons to Homegoing and Pachinko are fair, as those books are more family epics. I figured out the connection among the different characters, but I wished for more closure on one loose end—I suppose lack of closure is realistic, however. I was interested to learn that this novel came from the author’s dissertation research.

The Witch's Daughter (The Witch's Daughter, #1) by Paula Brackston

The Witch's Daughter (The Witch's Daughter, #1) by Paula Brackston Published by St. Martin's Griffin on December 1, 2008

Genres: Fantasy/Science Fiction, Historical Fiction

Pages: 387

Format: E-Book, eBook

Source: Library

Buy on Amazon, Buy on Bookshop

This post contains affiliate links you can use to purchase the book. If you buy the book using that link, I will receive a small commission from the sale.

Goodreads

THE NEW YORK TIMES BESTSELLER

An enthralling tale of modern witch Bess Hawksmith, a fiercely independent woman desperate to escape her cursed history who must confront the evil which has haunted her for centuries

My name is Elizabeth Anne Hawksmith, and my age is three hundred and eighty-four years. If you will listen, I will tell you a tale of witches. A tale of magic and love and loss. A story of how simple ignorance breeds fear, and how deadly that fear can be. Let me tell you what it means to be a witch.

In the spring of 1628, the Witchfinder of Wessex finds himself a true Witch. As Bess Hawksmith watches her mother swing from the Hanging Tree she knows that only one man can save her from the same fate: the Warlock Gideon Masters. Secluded at his cottage, Gideon instructs Bess, awakening formidable powers she didn't know she had. She couldn't have foreseen that even now, centuries later, he would be hunting her across time, determined to claim payment for saving her life.

In present-day England, Elizabeth has built a quiet life. She has spent the centuries in solitude, moving from place to place, surviving plagues, wars, and the heartbreak that comes with immortality. Her loneliness comes to an abrupt end when she is befriended by a teenage girl called Tegan. Against her better judgment, Elizabeth opens her heart to Tegan and begins teaching her the ways of the Hedge Witch. But will she be able to stand against Gideon—who will stop at nothing to reclaim her soul—in order to protect the girl who has become the daughter she never had?

I don’t understand the hate this one is getting on Goodreads. I put off reading it for something like a decade due to the low ratings! It’s actually pretty good. Parts of it are over the top, but the historical fiction aspects were well-researched and convincing, and I love a good story about someone who has lived through centuries of history. To me, that was the best part of Anne Rice’s books. I would read more of this author’s books for sure.

Time's Undoing by Cheryl A. Head

Time's Undoing by Cheryl A. Head Published by Dutton on March 7, 2023

Genres: Contemporary Fiction, Historical Fiction

Pages: 352

Format: E-Book, eBook

Source: Library

Buy on Amazon, Buy on Bookshop

This post contains affiliate links you can use to purchase the book. If you buy the book using that link, I will receive a small commission from the sale.

Goodreads

A searing and tender novel about a young Black journalist’s search for answers in the unsolved murder of her great-grandfather in segregated Birmingham, Alabama, decades ago—inspired by the author’s own family history

Birmingham, 1929: Robert Lee Harrington, a master carpenter, has just moved to Alabama to pursue a job opportunity, bringing along his pregnant wife and young daughter. Birmingham is in its heyday, known as the “Magic City” for its booming steel industry, and while Robert and his family find much to enjoy in the city’s busy markets and vibrant nightlife, it’s also a stronghold for the Klan. And with his beautiful, light-skinned wife and snazzy car, Robert begins to worry that he might be drawing the wrong kind of attention.

2019: Meghan McKenzie, the youngest reporter at the Detroit Free Press, has grown up hearing family lore about her great-grandfather’s murder—but no one knows the full story of what really happened back then, and his body was never found. Determined to find answers to her family’s long-buried tragedy and spurred by the urgency of the Black Lives Matter movement, Meghan travels to Birmingham. But as her investigation begins to uncover dark secrets that spider across both the city and time, her life may be in danger.

Inspired by true events, Time’s Undoing is both a passionate tale of one woman’s quest for the truth behind the racially motivated trauma that has haunted her family for generations and, as newfound friends and supporters in Birmingham rally around Meghan’s search, the uplifting story of a community coming together to fight for change.

This was a pretty good mystery. I liked the parts set in the present more; I think the author has a better feel for the present than the past. I thought the author handled the depiction of White allies with problematic families well. The book captures the setting extremely well; I feel certain the author has done a great deal of research.

The Sympathizer by

The Sympathizer by

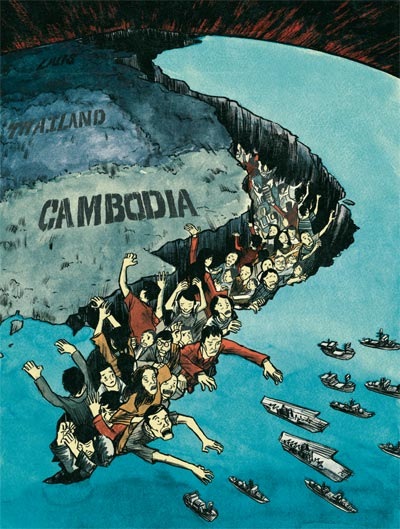

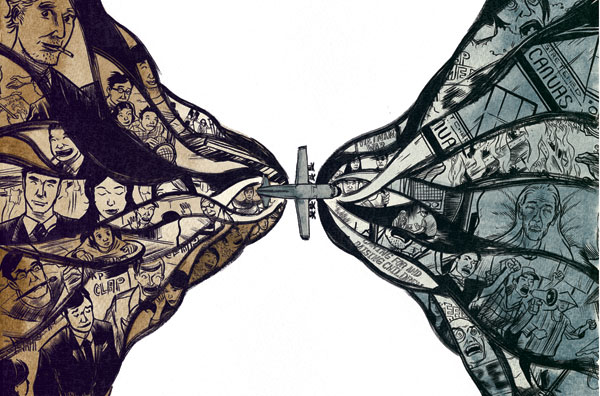

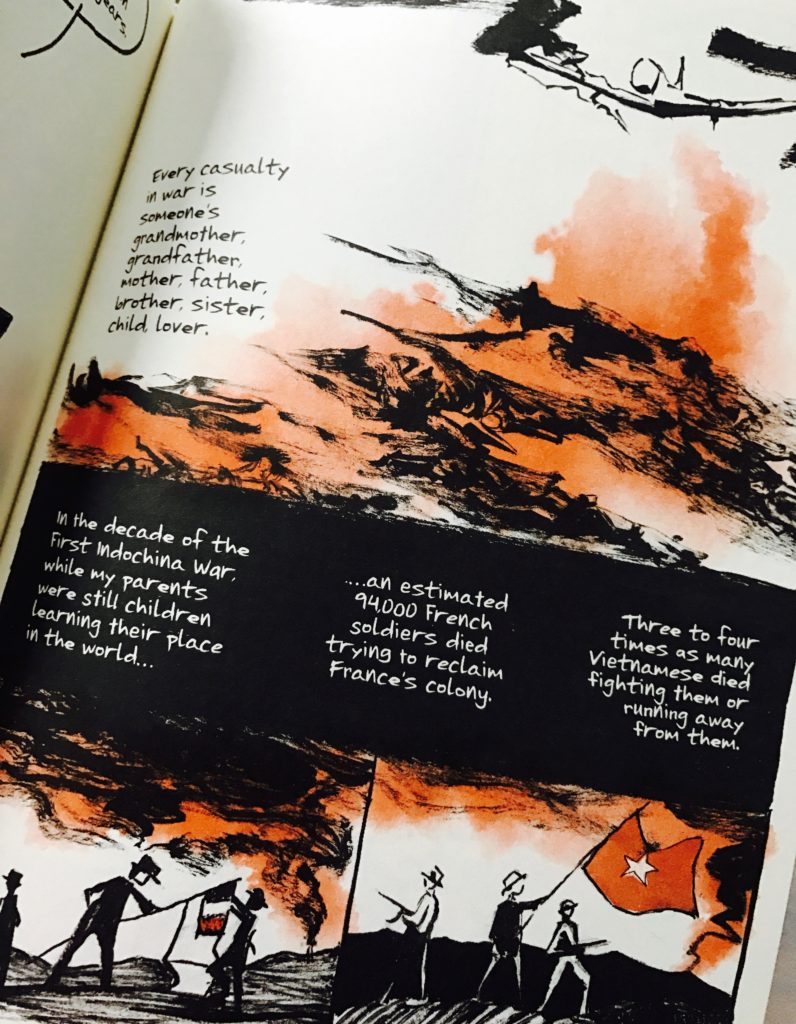

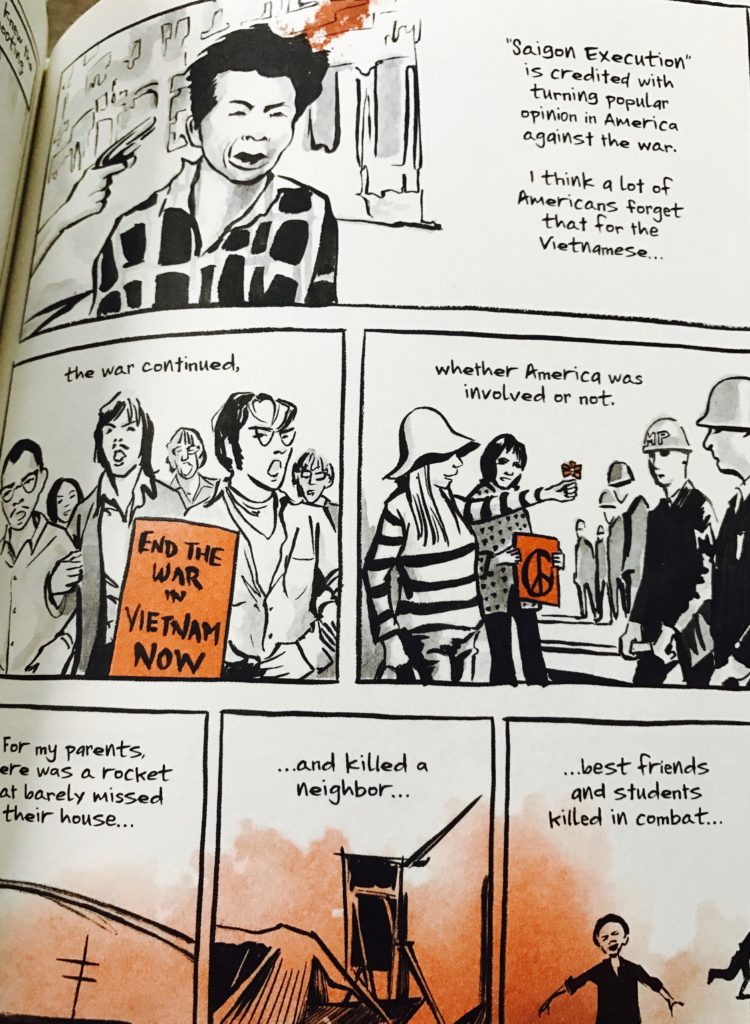

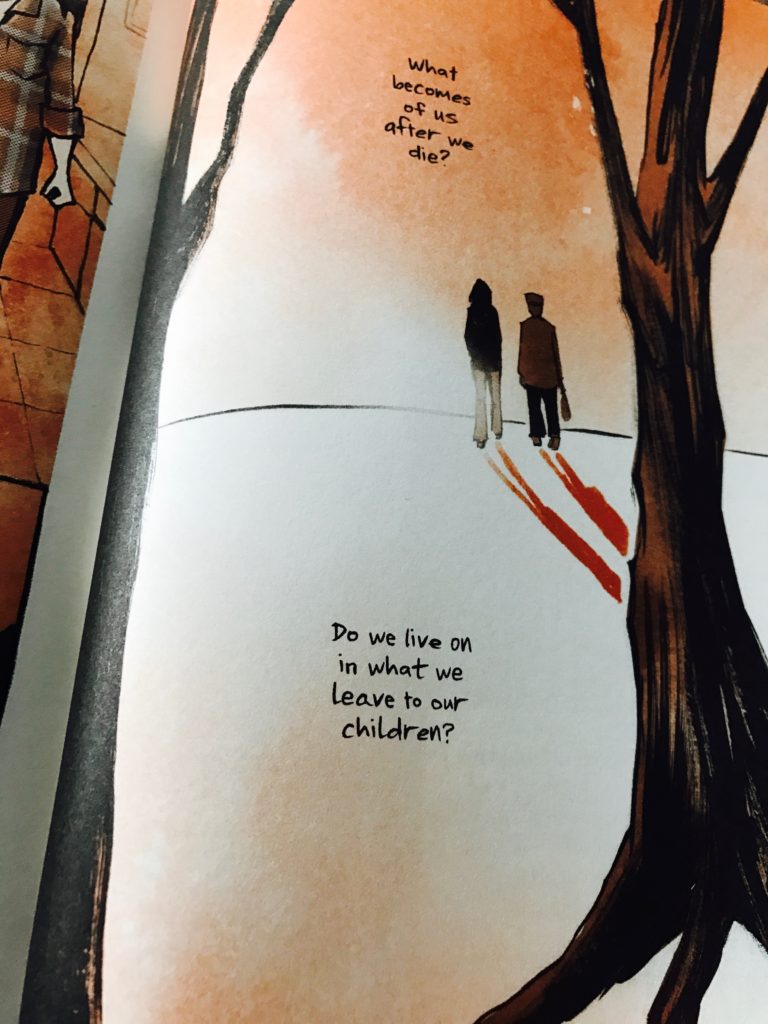

Tran’s artwork is captivating. He captures the chaotic scenes of Saigon and the evacuation of refugees particularly well. His use of color is deliberate and thoughtful. Scenes in the past are often muted shades of sepia and gray, while the present is generally drawn in brighter colors. I found it a little hard to keep track of the cast of characters at first, but by the end of the book, I had it figured out. Tran also captures well the feeling of the first generation American in a family of immigrants who have different histories, cultural ideals, and personal beliefs. I liked, for instance, his motif of his family’s celebration of Tet, a small way he shows the cultural gap he feels between his parents and himself.

Tran’s artwork is captivating. He captures the chaotic scenes of Saigon and the evacuation of refugees particularly well. His use of color is deliberate and thoughtful. Scenes in the past are often muted shades of sepia and gray, while the present is generally drawn in brighter colors. I found it a little hard to keep track of the cast of characters at first, but by the end of the book, I had it figured out. Tran also captures well the feeling of the first generation American in a family of immigrants who have different histories, cultural ideals, and personal beliefs. I liked, for instance, his motif of his family’s celebration of Tet, a small way he shows the cultural gap he feels between his parents and himself.