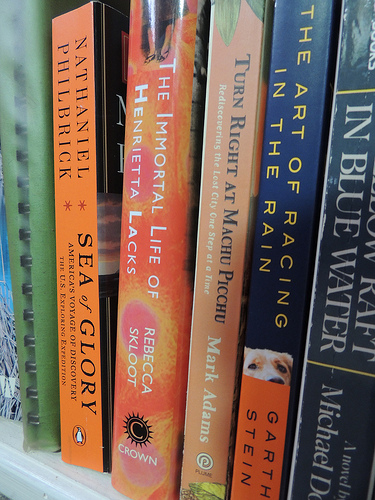

Americanah by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie

Americanah by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie Narrator: Adjoa Andoh

Published by Anchor on March 4th 2014

Genres: Contemporary Fiction

Pages: 589

Format: Audio, E-Book

Buy on Amazon

Goodreads

From the award-winning author of Half of a Yellow Sun, a powerful story of love, race and identity.

As teenagers in Lagos, Ifemelu and Obinze fall in love. Their Nigeria is under military dictatorship, and people are fleeing the country if they can. The self-assured Ifemelu departs for America. There she suffers defeats and triumphs, finds and loses relationships, all the while feeling the weight of something she never thought of back home: race. Obinze had hoped to join her, but post-9/11 America will not let him in, and he plunges into a dangerous, undocumented life in London.

Thirteen years later, Obinze is a wealthy man in a newly democratic Nigeria, while Ifemelu has achieved success as a blogger. But after so long apart and so many changes, will they find the courage to meet again, face to face?

Fearless, gripping, spanning three continents and numerous lives, Americanah is a richly told story of love and expectation set in today’s globalized world.

Third time’s a charm. I have tried to finish this book twice before, and I stalled out in about the same place both times. I decided to try to finish it this time because Carol Jago is leading a book club discussion of the book on Facebook for the National Council of Teachers of English members. I knew the problem with not being able to finish the book was me. Everyone I know who has read this book loved it, and I love Adichie, too, and I knew I should love this book. For some reason, I was just getting stuck right around the first part that focuses on Obinze. For what it’s worth, I do think the Obinze sections drag a bit, and I’m not sure why because his story is interesting, especially his sojourn as an undocumented immigrant in the UK.

When I was at lunch at work a couple of weeks ago, I complained about getting stuck with this book. One of the people listening to me complain asked me if I’d tried the audiobook. I listen to audio books all the time, but I had this one Kindle, so no, I hadn’t tried the audiobook, but I decided it might be just the thing to get me past being stuck. Once I got past that part, I admit I was riveted by the book. I was puttering around the house the last week or so, listening whenever I could.

One quibble I think I have with the book is the notion that Ifemelu’s blogs take off so quickly in popularity. I suppose some people get lucky in that regard, and yes, I’ve been approached for advertising on my education blog (which I don’t feel comfortable doing), but it seemed a bit unrealistic to me that her blogs both became so popular so fast. However, in the grand scheme of the book, this issue is so minor as to be nearly nonexistent. Adichie offers a thoughtful critique of race and class America, the UK, and Nigeria, as her characters explore their identities and struggle to make it as immigrants.

I understand a movie is in the offing, and that Lupita Nyong’o has been cast as Ifemelu and David Oyelowo as Obinze. The book could certainly make a good film, though I wonder how it will capture all the complexity of the novel. I could see teaching this novel at the college level, though I think it might be a bit too long for high school students, even in AP classes. However, it would offer wonderful opportunities for discussion with a class novel study. I would recommend this book to everyone, but I think white liberals especially have something to learn from this book.

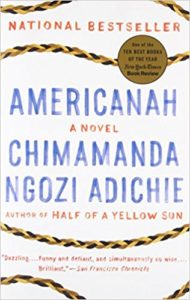

Homegoing by

Homegoing by

Sky in the Deep by

Sky in the Deep by

The Sympathizer by

The Sympathizer by

Murder on the Orient Express by

Murder on the Orient Express by  The Miniaturist by

The Miniaturist by

In the Shadow of the Banyan by

In the Shadow of the Banyan by

Alias Grace by

Alias Grace by