My favorite time of year! R.I.P. Time! Carl holds the R.I.P. (Readers Imbibing Peril) Challenge each year as fall descends in early September. The challenge ends each Halloween. The goal is to select a level of commitment, which Carl has dubbed Perils, and to read the required number of spooky books (and the definition of spooky is extremely broad).

My favorite time of year! R.I.P. Time! Carl holds the R.I.P. (Readers Imbibing Peril) Challenge each year as fall descends in early September. The challenge ends each Halloween. The goal is to select a level of commitment, which Carl has dubbed Perils, and to read the required number of spooky books (and the definition of spooky is extremely broad).

Peril the First involves reading four books of any length that fit the challenge.

Peril the Second involves reading two books of any length that fit the challenge.

Peril the Third involves reading one book of any length that fits the challenge.

Short Story Peril involves reading any number of short stories that fit the challenge.

Peril on the Screen involves watching films or television that fit the challenge.

Almost everyone can find a way to participate! I always over-commit myself and wind up not finishing the challenge, and I am going to finish this year! To that end, I’m going to commit to Peril the Second. If I can manage to fit in two more books, I’ll just up the level as I can. Even though I’ve never finished the challenge, I have enjoyed it each time.

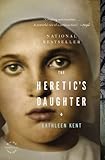

At this point, I am going to commit to reading Mockingjay by Suzanne Collins and The Heretic’s Daughter by Kathleen Kent. It’s YA dystopia and Salem witchcraft! Should be fun. If I read more, I’ll add them to the pile later on.