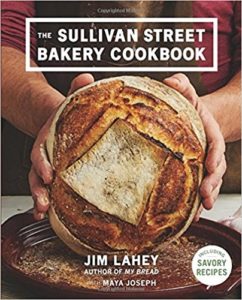

The Sullivan Street Bakery Cookbook by Jim Lahey, Maya Joseph, Squire Fox

The Sullivan Street Bakery Cookbook by Jim Lahey, Maya Joseph, Squire Fox Published by W. W. Norton Company on November 7th 2017

Genres: Cooking

Pages: 240

Format: Hardcover

Buy on Amazon

Goodreads

Founded in 1994, Sullivan Street Bakery is renowned for its outstanding bread, which graces the tables of New York’s most celebrated restaurants. The bread at Sullivan Street Bakery, crackling brown on the outside and light and aromatic on the inside, is inspired by the dark, crusty loaves that James Beard Award-winning baker Jim Lahey discovered in Rome.

Jim builds on the revolutionary no-knead recipe he developed for his first book, My Bread, to outline his no-fuss system for making sourdough at home. Applying his Italian-inspired method to his repertoire of pizzas, pastries, egg dishes, and café classics, The Sullivan Street Bakery Cookbook delivers the flavors of a bakery Ruth Reichl once called "a church of bread."

I think I ordered this book after reading about it on some sort of best-of-2017 cookbooks list. I am trying my hand at baking bread, and I really wanted to step up the challenge by trying sourdough baking. Back in December, I made my own sourdough starter using this recipe from King Arthur Flour. Jim Lahey includes his own starter recipe in The Sullivan Street Bakery Cookbook. I followed Lahey’s instructions to make my starter into biga, the stiff starter Lahey uses in many of his recipes. After I made my biga, I tucked it away in the refrigerator because I knew I wouldn’t have enough time to experiment with it. Lahey says that unlike regular starter, biga doesn’t need to be “fed” and will keep pretty much as long as you want it in the refrigerator.

I don’t know if it matters whether or not your biga is brought to room temperature after it’s been refrigerated, but I didn’t bother with it when I decided to try out the recipe for pane bianco, Lahey’s recipe for a no-knead sourdough bread. Until I used this recipe, the only sourdough bread I’d made was King Arthur’s sort of cheater recipe for “rustic” sourdough bread. I call it a cheater recipe because it uses yeast and doesn’t rely strictly on the sourdough starter to rise, which makes it good for beginners. It tastes fine, but I wasn’t happy with it. In looking through the recipes in Lahey’s book, I settled on the pane bianco because it seemed the least fiddly (there are a lot of very fiddly recipes in this book). Word of caution: it is extremely time-consuming—not in the amount of work you need to do, but in wait time.

Lahey’s instructions said that after combining the water and biga with the flour and salt the recipe calls for, you might need to wait anywhere from eight to eighteen hours for the bread to double in size. 😯 I decided to mix the dough the night before I would bake it so it could do its thing overnight. When I woke up, I checked the bread, and it seemed pretty much ready to go, so I followed Lahey’s instructions for shaping it and then letting it rise again. I have an enameled cast iron Dutch oven, and the instructions say not to heat it empty, but Lahey’s instructions say to preheat the Dutch oven. What to do? I didn’t want to risk damaging my Dutch oven, so I did some searching online and discovered I could put the bread into the Dutch oven, turn the oven on, and put the Dutch oven with the bread inside in the oven, which would serve basically the same function as preheating it while allowing the dough to finish its final rise. According to King Arthur’s blog, if you do this, you can just bake the bread according to its directions. I didn’t find this to be true. My crust came out quite a bit darker than I wanted it, as Lahey’s instructions say to bake the bread for 40 minutes. Next time, I will bake it for less time and see if that works better. The bread still turned out great.

I think given the fact that it was my first one, it really turned out better than expected. I forgot to slash the bread, which you are supposed to do with sourdough, but it didn’t seem to hurt anything.

I was really thrilled to see all the pockets of air. It truly tasted like one of those artisan loaves of bread you get at a bakery. I was ridiculously proud of being able to make a loaf of sourdough bread completely from scratch, using my very own biga created with my own starter. I have been intimidated by bread for a long time, and I credit buying Bread Toast Crumbs with being able to get over my fear of baking bread.

Lahey doesn’t like the tangy sourdough, so he says you don’t really taste that sourdough flavor in his recipes, and that was true of the bread I made. Keeping in mind this is the only recipe I have tried, I still recommend this book for people looking to step up their baking game. The recipes will offer a nice challenge for intermediate or more advanced bakers. It’s not a book for beginners, and be forewarned that most of the recipes will take time. We live in a busy world, and baking bread the old-fashioned way that Lahey uses takes a long time. Lahey also uses a kitchen scale and gives most of his instructions in grams. He gives you the volume measures as well but cautions that grams are better and more precise (and he’s right about that—I learned that lesson making soap). Bread is particularly picky and seems to work much better if you use a scale rather than trying to use measuring cups. It also matters if you are baking in the summer or winter, and you have to adjust. Thankfully, Lahey has good advice for how to adjust for seasonal temperature variances.

I know it’s sort of weird to read a recipe book all the way through, but Lahey’s personality and passion for baking come through, and even the recipes were entertaining to read. I used some of the techniques he describes in other recipes. For example, I found this great recipe for Detroit-style pizza with a homemade crust. After reading about how Lahey makes pizza dough look dimpled by “docking,” or pressing his fingers into the dough, I tried it with my pizza dough, and I achieved the same effect—”a sublime texture—pliant, soft, and bubbly” (119). For anyone curious about the pizza recipe, I make the pizza as is except I omit the cheddar cheese, which seems wrong on pizza to me, and use more mozzarella. I use both shredded mozzarella and fresh mozzarella cut into cubes. The results are pretty awesome.

There are a lot of recipes in the book I’m not sure I’d ever try (that panettone seems incredibly daunting for something I’m not even sure I’d like), but the bread recipes look good, the breakfasts look tasty, and the pizza crust is definitely on my to-d0 list.

I ordered Lahey’s first book My Bread this afternoon because I liked this book so much. I kind of want to visit his bakery if I get a chance to go to New York.

Murder on the Orient Express by

Murder on the Orient Express by

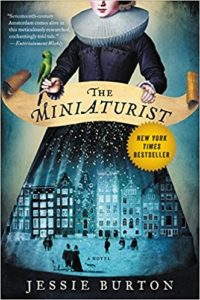

The Miniaturist by

The Miniaturist by

The House of the Seven Gables by

The House of the Seven Gables by

A Wrinkle in Time (Time Quintet, #1) by

A Wrinkle in Time (Time Quintet, #1) by

Stonewall by

Stonewall by

In the Shadow of the Banyan by

In the Shadow of the Banyan by

Alias Grace by

Alias Grace by