Before I discuss the contents of Chrissie Hynde’s memoir, Reckless: My Life as a Pretender, I need to get two things out of the way: 1) I am kind of a sucker for rock memoirs, which is something that started in my teens when I checked several books on the subject out of the library, and 2) I really like the Pretenders. I started really listening to them in college. I especially liked earlier records—their first two eponymously titled albums and Learning to Crawl. I once got a haircut I really hated, but then someone told it made me look like Chrissie Hynde, and I didn’t hate it anymore. Enjoying Chrissie Hynde’s music, however, didn’t mean I thought she walked on water. Quite the contrary. Before I picked up this book, I had certainly read enough about her and read enough of her interviews to know she isn’t someone I’d necessarily like very much. I don’t need to like someone’s personality to enjoy their art. I read an interview with Martin Freeman, for example, that left me scratching my head and wondering if he is truly a jerk or was just in bad mood. But I love him on film.

Hynde quite literally begins her memoir at the beginning, with her early years living in Akron. She loved listening to music, and living near Cleveland, which has always been a big rock and roll city, gave her easy access to the music she loved. She describes her misadventures attempting to please her parents and matriculate at Kent State—she knew one of the young men who was killed in 1970. She left Ohio for London just as the punk scene was starting and knew many of the major players, including Malcolm McLaren and Vivienne Westwood (she worked in their shop), the Sex Pistols, the Clash, and the Damned, among others. She seems to have spent most of her twenties focused on getting into a band and taking drugs. She does mention that the memoir would focus on her drug abuse, and it does. Caveat emptor for those looking to learn more about the Pretenders. Aside from the first two albums and the early years of the band, she does not tell that story in these pages. One wonders if something of her passion for the band and its music died with James Honeyman-Scott, the Pretenders’ first guitarist, in 1982. Neither of her spouses even gets a mention, and her relationship with Ray Davies rates only a few pages. Hynde waxes most lyrical at the end, when she discusses how “Jimmy’s” death affected her.

I can’t say I really disliked this book, but I didn’t like it, really, either. Hynde’s cast of characters was hard for me to keep straight, and I could have used a glossary of names or something. Hynde has certainly had some interesting experiences, and she is unflinching in her description, even if her story puts her in a bad light. She has said a couple of controversial things about possible rape (and certainly some kind of sexual assault) she experienced, namely, that she blames herself for getting into the situations in which she has been abused.

Now, let me assure you that, technically speaking, however you want to look at it, this was my doing and I take full responsibility. You can’t fuck around with people, especially people who wear “I Heart Rape” and “On Your Knees” badges. (119)

Hynde may indeed have been under the influence of drugs, and she may have made some poor decisions, but it makes me sad that she comes across as feeling like she somehow deserved to be assaulted because of these decisions. She was raised in an era when women were often blamed for their own rapes (Just how short was your skirt?), but she would, one hopes, be more enlightened now. Or maybe not. It would be nice if we lived in a world in which instead of minding ourselves and doing what we can to avoid being raped, men just didn’t, you know, rape people. Victim-blaming seems to be worst when it comes to these kinds of cases, though, and sometimes even the victims blame themselves. I have ready Hynde’s interviews on this topic, and she is quite heated, even insisting people don’t buy her book if they don’t want to read her story as she wants to tell it.

I can’t really figure her out. She comes off in interviews as brittle, and her frequent digs at people who choose not to be vegetarians are also off-putting. But I can’t deny she has swagger, and she did create some good music. I am glad she was able to stop taking drugs. I’m sad it took the deaths of two bandmates to determine she needed to get clean. I wish she had talked more about her experiences after 1982 as well. I also wish she didn’t feel the need to insult teachers every time it’s necessary to her memoir to mention teachers or education. I have read reviews calling this memoir “well-written.” I wouldn’t go that far. It’s not badly written. The prose is passable, with the exception of Hynde’s fondness for exclamation points. It’s also really not well organized. She flits around in time in a way that’s not easy to follow, and individual chapters can be anything from focused on a single event to wildly chaotic romps through years of time. If only she had paid a bit more attention to those teachers she finds it necessary to denigrate. Ah well. She didn’t need to, in the end, because she had a brilliant career in rock. I just wish I’d been able to read more about it. Unless you’re a big fan, I’d recommend skipping this book and listening to the Pretenders’ music instead. Even if you are a big fan, it’s still not too bad of an idea to skip this one in favor of of the music.

Rating:

I no longer remember how long this book’s been on my backlist, but it’s been a while. Maybe even when it first came out. I decided to count to for the Beat the Backlist Challenge.

I no longer remember how long this book’s been on my backlist, but it’s been a while. Maybe even when it first came out. I decided to count to for the Beat the Backlist Challenge.

I am also counting this one toward the Wild Goose Chase Challenge for the category of a book with a word or phrase relating to “wildness” in the title. You can’t pass up pairing “wild” with “reckless,” and one thing I can say for sure: Chrissie Hynde is wild.

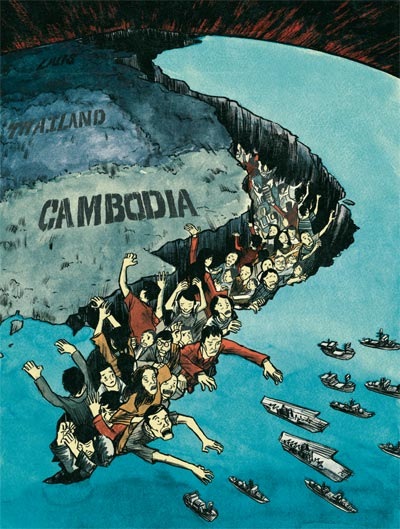

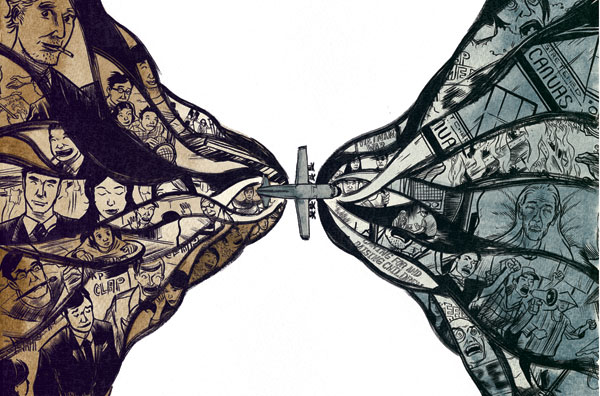

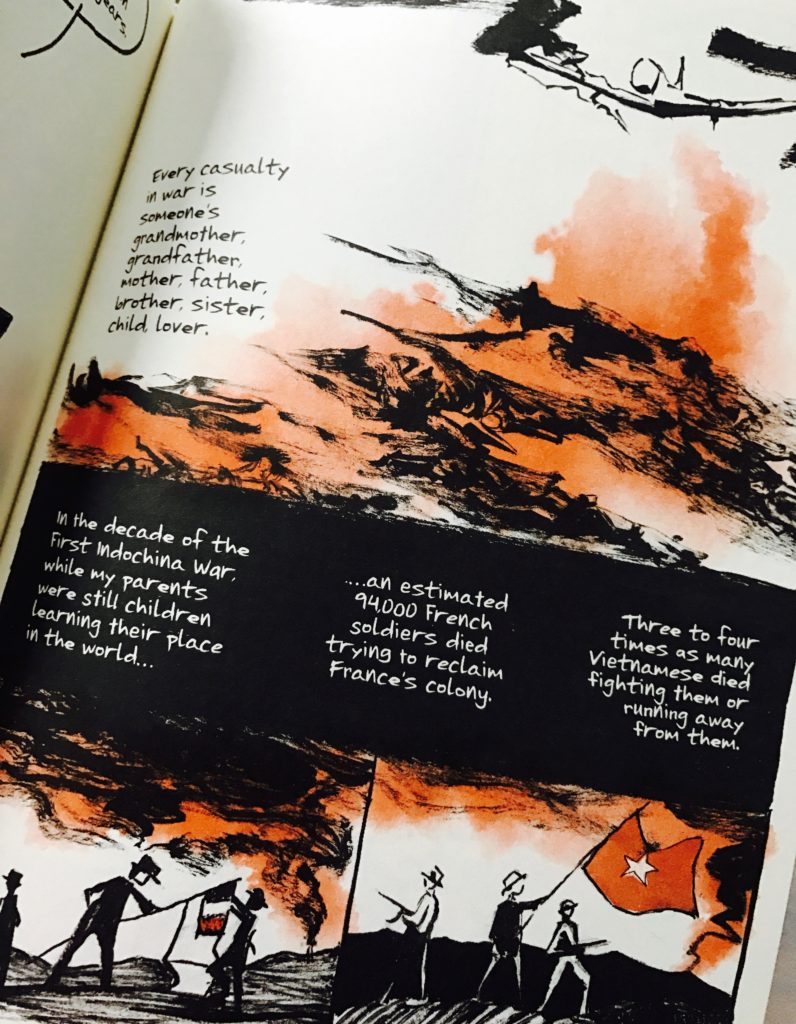

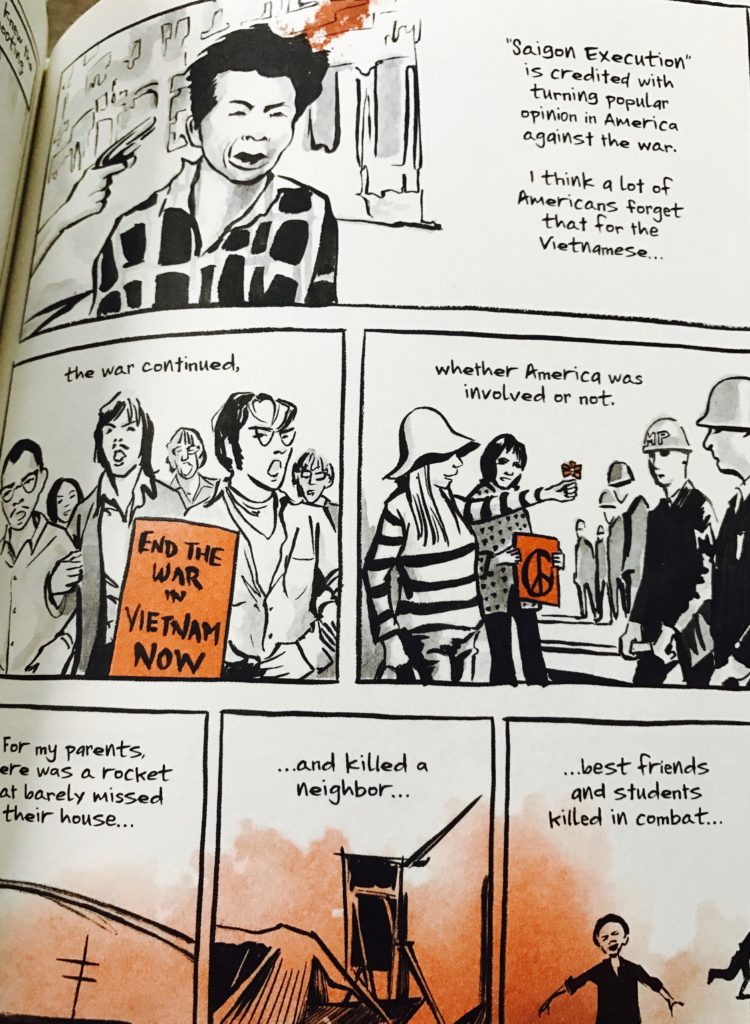

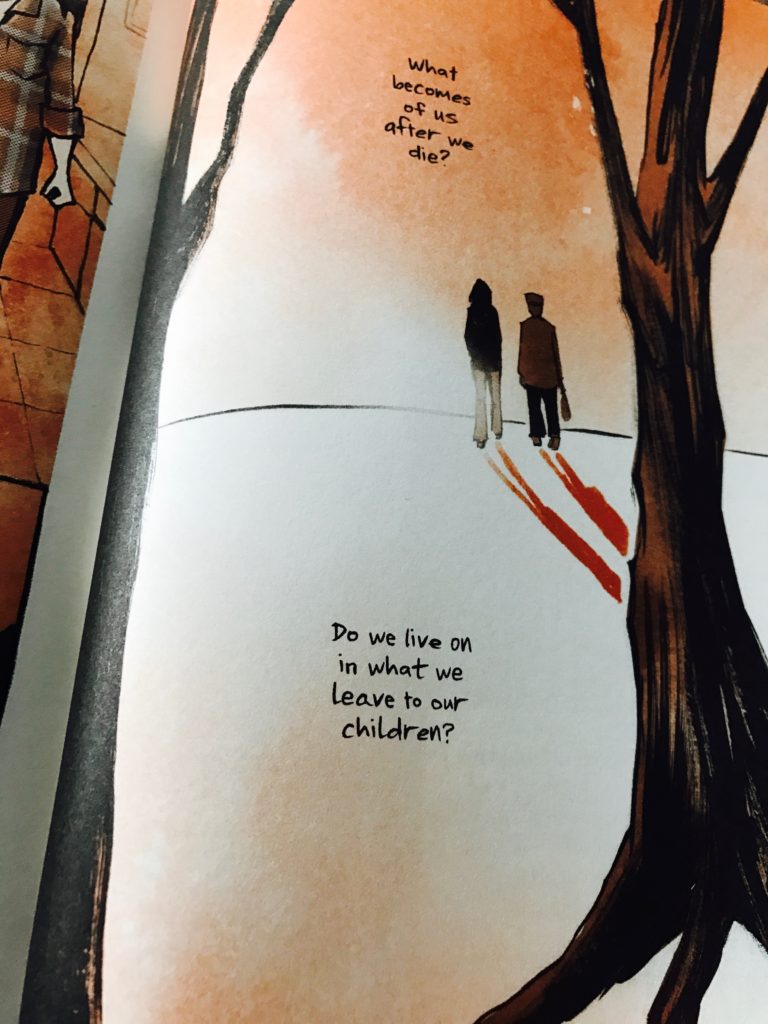

Tran’s artwork is captivating. He captures the chaotic scenes of Saigon and the evacuation of refugees particularly well. His use of color is deliberate and thoughtful. Scenes in the past are often muted shades of sepia and gray, while the present is generally drawn in brighter colors. I found it a little hard to keep track of the cast of characters at first, but by the end of the book, I had it figured out. Tran also captures well the feeling of the first generation American in a family of immigrants who have different histories, cultural ideals, and personal beliefs. I liked, for instance, his motif of his family’s celebration of Tet, a small way he shows the cultural gap he feels between his parents and himself.

Tran’s artwork is captivating. He captures the chaotic scenes of Saigon and the evacuation of refugees particularly well. His use of color is deliberate and thoughtful. Scenes in the past are often muted shades of sepia and gray, while the present is generally drawn in brighter colors. I found it a little hard to keep track of the cast of characters at first, but by the end of the book, I had it figured out. Tran also captures well the feeling of the first generation American in a family of immigrants who have different histories, cultural ideals, and personal beliefs. I liked, for instance, his motif of his family’s celebration of Tet, a small way he shows the cultural gap he feels between his parents and himself.