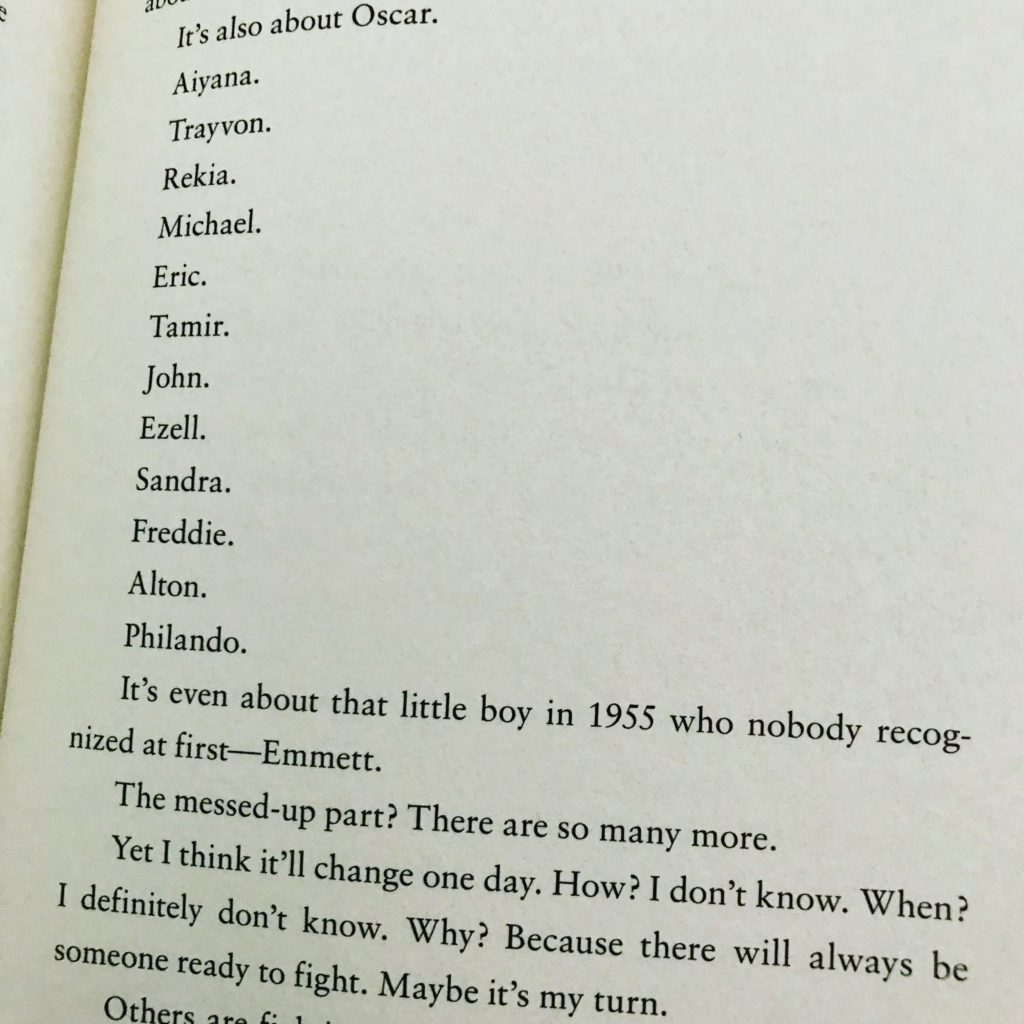

Ta-Nehisi Coates’s newest book We Were Eight Years in Power is a collection of essays written over the eight years of Barack Obama’s presidency. Most were published in The Atlantic, where Coates has been making waves as “America’s best writer on race,” an assessment he admits makes him “retch” (117). He doesn’t explicitly say so, but I suppose it’s partly the fact that so many white people turn to him as the authority, the purveyor of “the black perspective.” I wonder if he feels like, as a character in The Freedom Writers claims, “the Rosetta Stone of black people.” He asks, “Why do white people like what I write?” (118). He admits that this “voice inside” him, this question, would “eventually overshadow the work, or maybe it would just feel like it did” (118). I would argue he is one of the most lucid and persuasive writers of his generation, and perhaps because of it, he has attracted an audience he didn’t necessarily believe he would attract. It’s clear he is confused by this attention, but one need only read the pages of We Were Eight Years in Power to understand why the attention confuses him. He is accustomed to a white America that does not listen to the complete story of itself. It believes its own myths. He has a gift for laying those myths bare and reminding us to consider what we would prefer to forget.

Coates writes a preface to each essay, except for the last, “The First White President,” which serves as an epilogue. In his prefaces, he discusses where his mind was at the time of writing the essay, what his process was like, and how he views the work now. It’s as much about writing as it is about issues of race in the time of America’s first black president.

The title comes from Thomas Miller, an African American congressman who served South Carolina during the South’s period of Reconstruction:

We were eight years in power. We had built schoolhouses, established charitable institutions, built and maintained the penitentiary system, provided for the education of the deaf and dumb, rebuilt the ferries. In short, we had reconstructed the State and placed it upon the road to prosperity. (xiii)

Coates saw parallels between Miller’s disbelieving appeal and Barack Obama’s legacy as the first black president. Certainly, Coates seems to capture our times in ways that few writers can. The prefaces to each essay are the writer at the height of his critical powers, both of his own work and of the current historical moment.

Of the collected essays, I agree with Coates’s assessment regarding “The Case for Reparations”: “I thought I was at my best when I could combine the reporting and the essay. ‘The Case for Reparations’ is, for that reason, the best piece in this volume to my mind” (288). I had been meaning to read that essay for years and even carried a printout of the article as it appeared in The Atlantic in my school bag for a long time, but I did not actually read it until I read this book. It’s a powerhouse of research and writing. However, all of the essays made me think and challenged what I understood to be true from my perspective as a white woman. If I have one quibble with the book, it’s that I think Coates does not consider sexism at all when he deconstructs Donald Trump’s election win in “The First White President.” He seems to ascribe Hillary Clinton’s defeat entirely to racist backlash against Barack Obama, as she would have cemented his legacy. While it’s true that Obama supported Hillary Clinton’s campaign, and it’s probably true that racism played a large part in her defeat as voters heard Trump’s promises to undo all that Obama had done, it’s impossible to say that racism is entirely to blame. Had Hillary Clinton been a man with all the same qualifications she possesses, I think she’d be president now. She did win the popular vote, and I believe that she would also have won the electoral vote if she were a man. None of that is to say that Coates’s analysis doesn’t bear thinking about. Perhaps many people haven’t thought hard enough about just how much of a role racism played in that election since the two major party candidates are both white. This quibble does not mean I felt the book needed to lose any stars in my rating, however. Coates has a brilliant mind.

I found it interesting to read about Coates’s struggles as a writer, and I want to share this selection from an interview he gave about writing and the writing process.

As a writer myself, I found it incredibly heartening to hear such a gifted writer discuss his struggles with the craft.

If you are concerned about social justice issues and racism in our current moment and across the broad swathe of American history, you need to read this book. It’s a book I wish all Americans would read and think about.

Rating: