How the Word Is Passed: A Reckoning with the History of Slavery Across America by Clint Smith

How the Word Is Passed: A Reckoning with the History of Slavery Across America by Clint Smith on June 1, 2021

Genres: History

Pages: 352

Format: Hardcover

Buy on Amazon

Goodreads

Poet and contributor to The Atlantic Clint Smith’s revealing, contemporary portrait of America as a slave-owning nation.

Beginning in his own hometown of New Orleans, Clint Smith leads the reader through an unforgettable tour of monuments and landmarks—those that are honest about the past and those that are not—that offer an intergenerational story of how slavery has been central in shaping our nation's collective history, and ourselves.

It is the story of the Monticello Plantation in Virginia, the estate where Thomas Jefferson wrote letters espousing the urgent need for liberty while enslaving over 400 people on the premises. It is the story of the Whitney Plantation, one of the only former plantations devoted to preserving the experience of the enslaved people whose lives and work sustained it. It is the story of Angola Prison in Louisiana, a former plantation named for the country from which most of its enslaved people arrived and which has since become one of the most gruesome maximum-security prisons in the world. And it is the story of Blandford Cemetery, the final resting place of tens of thousands of Confederate soldiers.

In a deeply researched and transporting exploration of the legacy of slavery and its imprint on centuries of American history, How the Word Is Passed illustrates how some of our country's most essential stories are hidden in plain view-whether in places we might drive by on our way to work, holidays such as Juneteenth, or entire neighborhoods—like downtown Manhattan—on which the brutal history of the trade in enslaved men, women and children has been deeply imprinted.

Informed by scholarship and brought alive by the story of people living today, Clint Smith’s debut work of nonfiction is a landmark work of reflection and insight that offers a new understanding of the hopeful role that memory and history can play in understanding our country.

This is a fascinating book and a must-read for, well, everyone. In the pages of this book, Clint Smith embarks on a journey to several sites associated with slavery and racism and shares the stories of those sites and how their past is either reckoned with or isn’t. For a taste, you might consider reading Smith’s recent article in The Atlantic: “Why Confederate Lies Live On.” For another, more poetic taste, check out this poem:

In the book’s Epilogue, Smith writes that we are not as removed from the history of slavery and racism as some of us would like to pretend. Recalling a story his grandmother told him about White children throwing food at her from their bus as she walked, he writes, “The children who threw food at my grandmother and called her a n***** are likely bouncing their own great-grandchildren on their laps” (288). I know for a fact that they are because I was raised by them, as hard as it is for me to say. I love some of my family and they have been and in some cases still are deeply racist. Part of the reason that racism persists is ignorance. So much of the truth of what really happened was not taught in schools. I know I didn’t learn it. I do think more efforts are made now to try to right that wrong, but many states are also engaged in a fierce battle—at this very moment—to prevent teachers from teaching students the truth about slavery and racism.

Learning the truth about this country could be cleansing and freeing, but there is so much fear. As Smith argues, students “knowing their history helps them more effectively identify the lies” they are told about their history and their present (262). Ultimately, Smith’s thesis is that if we know the truth, we can heal and move forward, but if we continue to remain ignorant, then our societal problems due to racism will persist.

Smith’s writing is lyrical and beautiful at times. Smith’s background as a poet is on full display in some of the language he uses. He begins the book by calling on readers to listen. In his Prologue, he uses language such as “congregation,” “crowd,” and “gathered” to call his audience together to hear what he has learned in his travels to Monticello, the Whitney Plantation, Angola Prison, Blandford Cemetery, Galveston, New York City, and Gorée Island (Senegal), finally ending with his grandparents’ stories. Smith makes the clear argument that history is us; we caused it to happen, and we can change its course.

I can’t recommend this book highly enough.

Four Hundred Souls: A Community History of African America, 1619-2019 by

Four Hundred Souls: A Community History of African America, 1619-2019 by  Never Caught: The Washingtons' Relentless Pursuit of Their Runaway Slave, Ona Judge by

Never Caught: The Washingtons' Relentless Pursuit of Their Runaway Slave, Ona Judge by

The Heartbeat of Wounded Knee: Native America from 1890 to the Present by

The Heartbeat of Wounded Knee: Native America from 1890 to the Present by

Killers of the Flower Moon: The Osage Murders and the Birth of the FBI by

Killers of the Flower Moon: The Osage Murders and the Birth of the FBI by

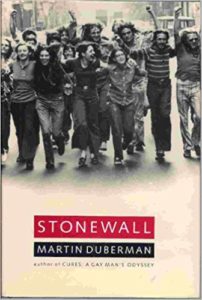

Stonewall by

Stonewall by