In honor of Father’s Day, I thought I’d pull together my own list of the top five dads in literature.

Happy Fathers’ Day to all those dads, but especially to my husband, Steve Huff; my dad, Tom Swier; and my grandfather, Udell Cunningham.

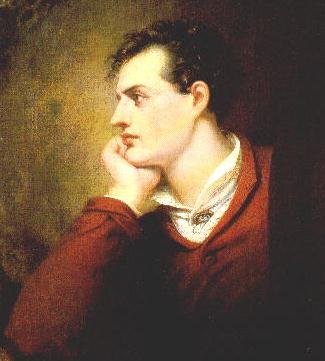

Atticus Finch. Probably first on any list of great literary dads, Atticus Finch of [amazon_link id=”0061205699″ target=”_blank” ]To Kill a Mockingbird[/amazon_link] showed his children through example why doing the right thing is always best, even if it isn’t easy, and that there are all kinds of bravery. Atticus is believed to be based on Harper Lee’s own father Amasa Lee. Harper Lee gave Gregory Peck (pictured above with Mary Badham as Scout), who played Atticus in the film of [amazon_link id=”0783225857″ target=”_blank” ]To Kill a Mockingbird[/amazon_link], her father’s pocket watch.

Arthur Weasley. The beloved patriarch of the Weasley family in the [amazon_link id=”0545162076″ target=”_blank” ]Harry Potter[/amazon_link] series, Arthur Weasley is a role model to his children and a father figure to their friend, Harry. He is brave, loyal, hardworking, and fair-minded. Some readers may not know that J. K. Rowling considered writing Arthur Weasley’s death into [amazon_link id=”0439358078″ target=”_blank” ]Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix[/amazon_link], but he was given a reprieve when Rowling realized losing his father would alter Ron’s personality in ways that wouldn’t work for the character.

Señor Sempere. Father of Daniel Sempere in [amazon_link id=”0143034901″ target=”_blank” ]The Shadow of the Wind[/amazon_link], Señor Sempere was a bookseller who took his son to the Cemetery of Forgotten Books to adopt a book. The elder Sempere is the only parent young Daniel has after his mother’s death, and he sacrifices to buy him Victor Hugo’s pen.

Mr. Bennet. Hear me out on this one. [amazon_link id=”1936594293″ target=”_blank” ]Pride And Prejudice‘s[/amazon_link] Mr. Bennet has his faults. He lets Lydia and Kitty run wild. He holes himself up in his study on a regular basis. On the other hand, he loves Elizabeth and encourages her to marry for love. On Mr. Collins’s proposal, after Mrs. Bennet tries to enlist Mr. Bennet’s help in making Elizabeth see reason, he says, “An unhappy alternative is before you, Elizabeth. From this day you must be a stranger to one of your parents. Your mother will never see you again if you do not marry Mr. Collins, and I will never see you again if you do.”

Robert Quimby. Ramona’s dad is awesome. In [amazon_link id=”0380709163″ target=”_blank” ]Ramona and Her Father[/amazon_link], Ramona’s dad loses his job and her mother goes to work. One of the most heartwarming episodes in children’s literature is the chapter in which the Quimby family can finally splurge and go out for hamburgers, and a nice elderly man at another table pays for their meal. Having been the recipient of this exact kindness myself, I can tell you how much it means.

Who do you think the best dads in literature are?

How much am I enjoying Jude Morgan’s novel

How much am I enjoying Jude Morgan’s novel