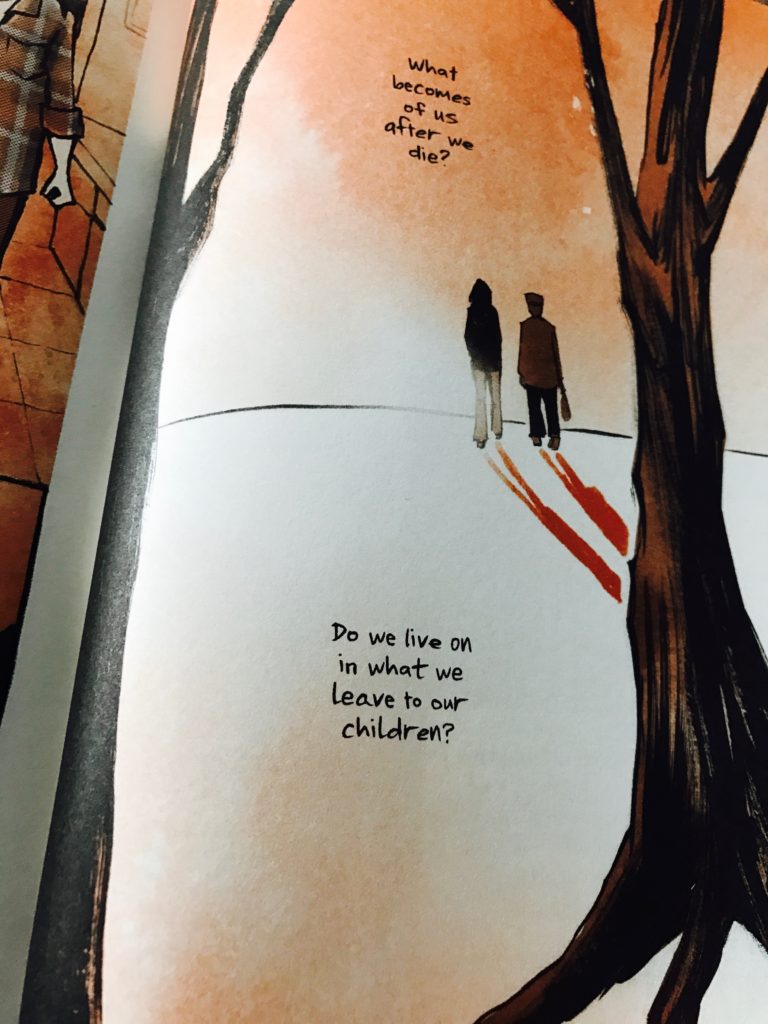

Thi Bui’s graphic memoir The Best We Could Do was just released last week. Bui was born in Vietnam in the waning days of the Vietnam War. She was only a few months old on April 30, 1975 when Saigon fell. She begins her narrative with the difficult birth of her son, then flashes back to her own mother’s difficult birth of her younger brother in a refugee camp in Malaysia. Bui’s family eventually settled in California, and with beautiful artwork on every page, Bui movingly details her family’s story, starting with her parents’ childhoods contrasted with her own. Unflinchingly honest, Bui’s memoir is a must-read.

I grew up hearing what Bui calls the “oversimplification and stereotypes in American versions of the Vietnam War.” My father was stationed at Cam Ranh Bay when I was born, but he was in the Air Force, and as far as I know (and I think he’d have told me), he didn’t engage in combat. It was some time before a body of literature about this war started to published, and I think most people are guilty of listening to and perhaps even believing what Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie calls “the single story”—that incomplete story of a people based on few examples in literature.

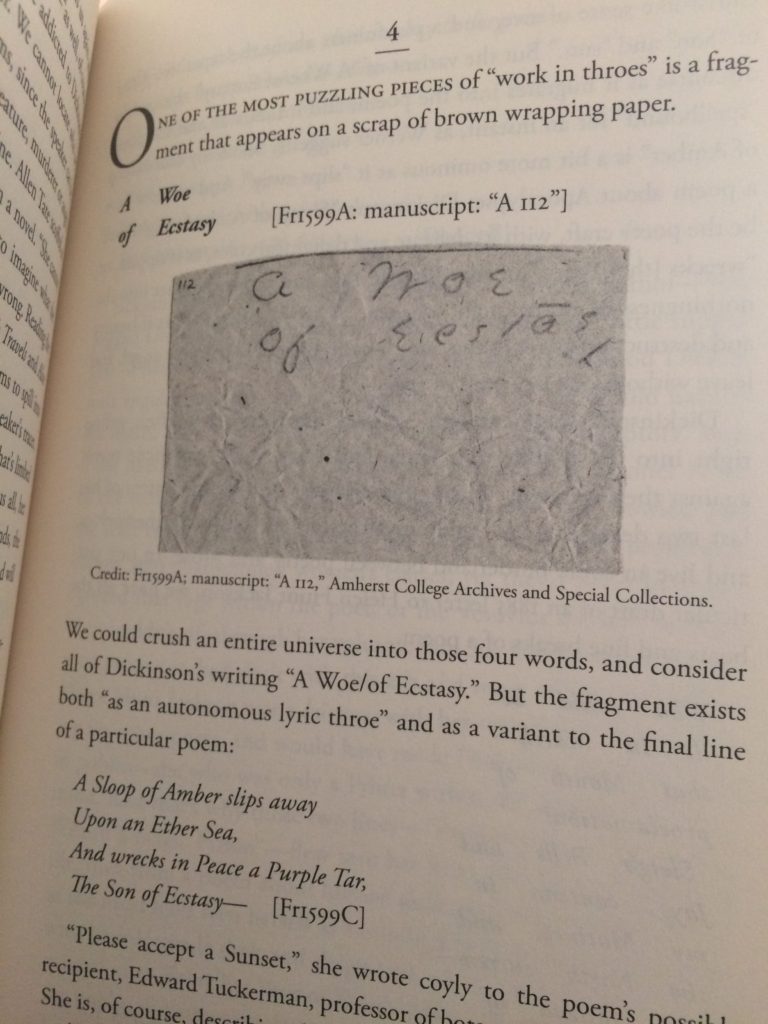

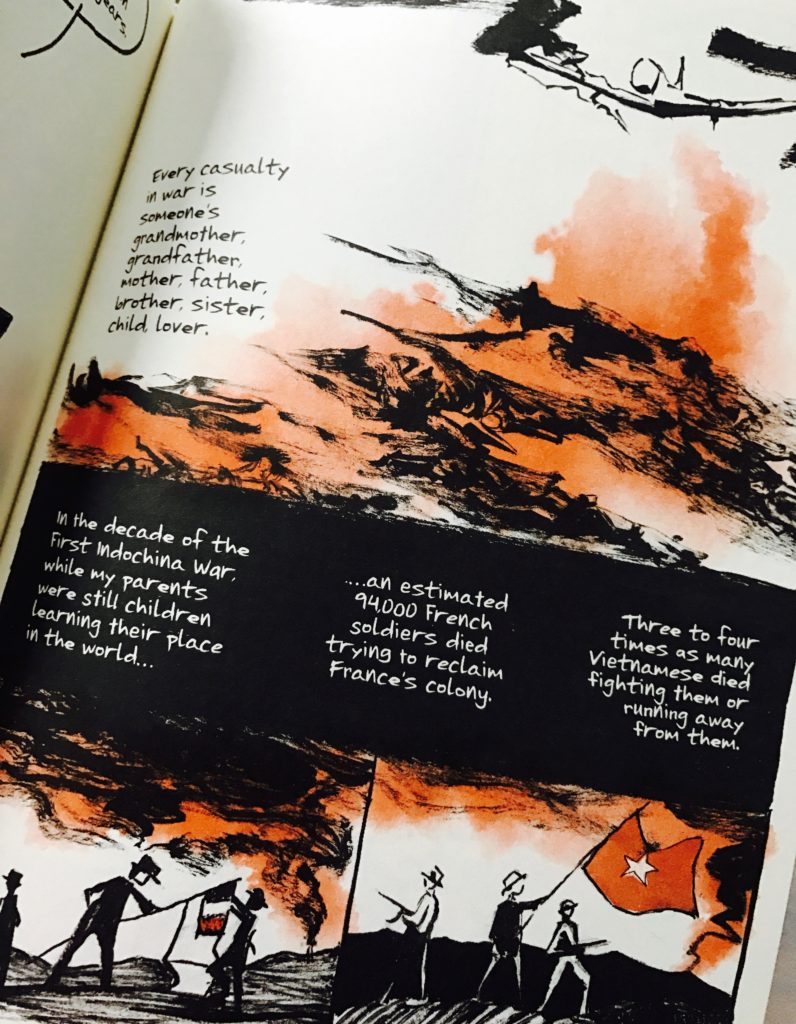

But at Bui says, we tend to forget—to our peril—that “[e]very casualty in war is someone’s grandmother, grandfather, mother, father, brother, sister, child, lover.” Many times in history, as we know too well, the voices of the casualties have been silenced. Their narrative has not been heard.

And I think one big thing we forget is that the Vietnam War continued after America decided to stop fighting. America’s involvement was on the wane when my father served in 1971. America withdrew from the war in 1973, a full two years before the war ended.

Bui is at her best in this memoir when she puzzles over contradictions and tries to make sense of her past and her family’s past, which is also how she explains why she needed to write this book.

The Best We Could Do will surely draw comparisons to Maus and Persepolis. I also recently read Vietnamerica, and while GB Tran’s story is entirely different from Bui’s, reading both of them gave me more stories about what Vietnam and the Vietnam War were like through the eyes of a family who were just doing the best they could do. The arresting images coupled with the narrative make for a gut-wrenching read. The book is gorgeous, as well. The paper is high quality, and the dust cover is thick, heavy paper. I didn’t try to read the electronic version, but my gut tells me this book needs to be experienced in print to be enjoyed fully. A remarkable read.

Rating:

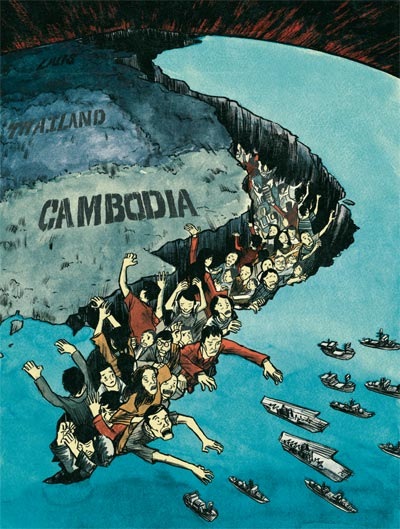

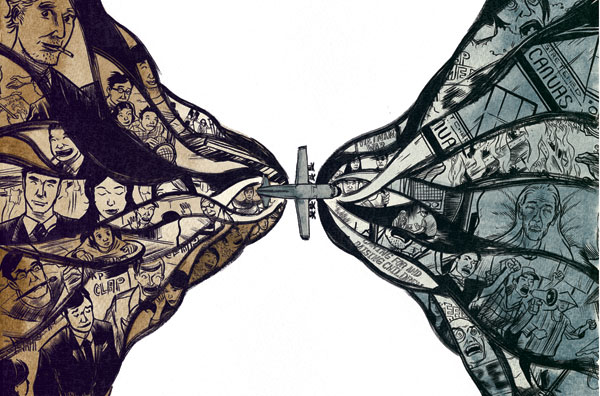

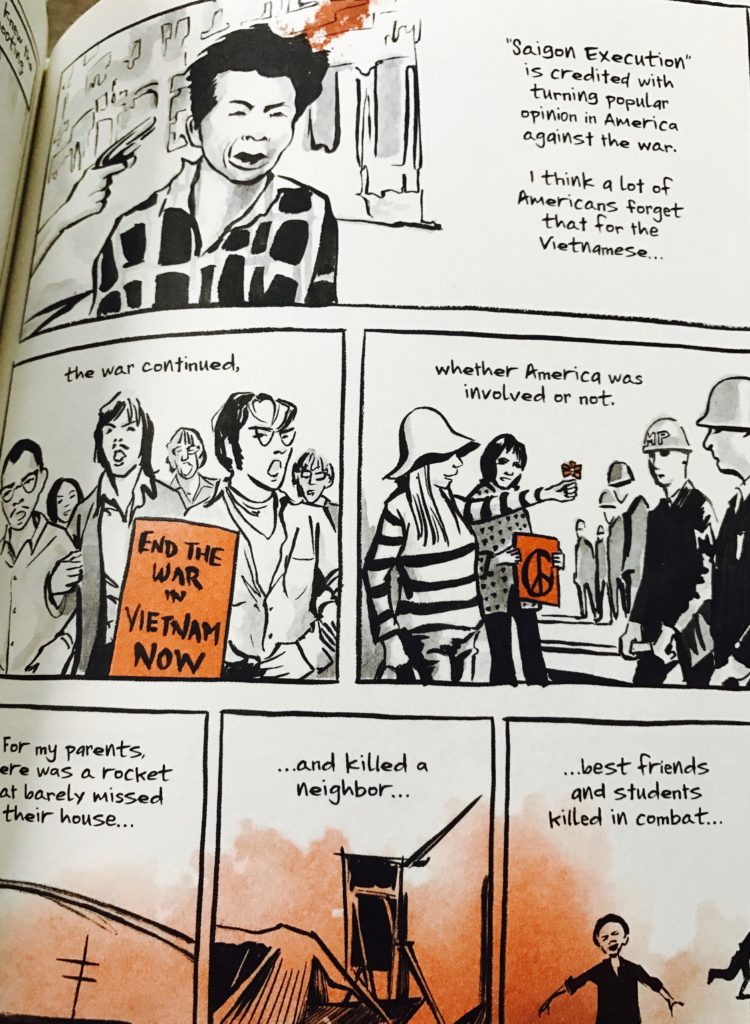

Tran’s artwork is captivating. He captures the chaotic scenes of Saigon and the evacuation of refugees particularly well. His use of color is deliberate and thoughtful. Scenes in the past are often muted shades of sepia and gray, while the present is generally drawn in brighter colors. I found it a little hard to keep track of the cast of characters at first, but by the end of the book, I had it figured out. Tran also captures well the feeling of the first generation American in a family of immigrants who have different histories, cultural ideals, and personal beliefs. I liked, for instance, his motif of his family’s celebration of Tet, a small way he shows the cultural gap he feels between his parents and himself.

Tran’s artwork is captivating. He captures the chaotic scenes of Saigon and the evacuation of refugees particularly well. His use of color is deliberate and thoughtful. Scenes in the past are often muted shades of sepia and gray, while the present is generally drawn in brighter colors. I found it a little hard to keep track of the cast of characters at first, but by the end of the book, I had it figured out. Tran also captures well the feeling of the first generation American in a family of immigrants who have different histories, cultural ideals, and personal beliefs. I liked, for instance, his motif of his family’s celebration of Tet, a small way he shows the cultural gap he feels between his parents and himself.