Emily St. John Mandel’s fourth novel Station Eleven is probably not a book I’d have picked up if it hadn’t been recommended to me, and what I would have missed!

Emily St. John Mandel’s fourth novel Station Eleven is probably not a book I’d have picked up if it hadn’t been recommended to me, and what I would have missed!

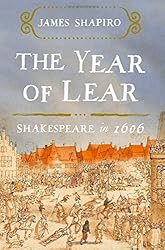

Station Eleven is a layered novel about the world twenty years after the apocalypse. A virulent new strain of the flu almost completely obliterates the population of the earth. Kirsten was about eight years old when the flu struck. She had been acting in a production of King Lear on the night when the flu landed in Toronto, where the novel begins. The lead actor is suddenly stricken with a heart attack and dies onstage. Twenty years later, Kirsten is traveling with a symphony/Shakespearean acting troupe that has a circuit in the Great Lakes area, bringing art and entertainment to the small communities created in the wake of the Georgian flu because “survival is insufficient.” The novel connects the stories of Kirsten, the lead actor Arthur, the man who tries to save Arthur’s life, and Arthur’s friends and family.

Wow. This book was amazing. I didn’t want to put it down, and I almost stayed up really late last night to finish it, but I made myself stop reading so I wouldn’t be dragging today at work. It would be easy for some readers to say they’re tired of dystopian fiction or to say they don’t like science fiction and dismiss this book, but the book is not like the typical dystopian or sci-fi novel I’ve read. In fact, I understand that Mandel doesn’t really classify the novel in those genres herself. The balancing act Mandel must do by weaving the various threads together and by linking the themes is fascinating to watch in terms of the writing craft. She pulls it off. Most dystopian novels deal with the immediate aftermath of an apocalypse or dwell only in the darkest parts of the world left behind. Mandel sees a bit more hope for humanity than that. Even in the darkest times and places, people have created art so that they can feel human. I was reminded of the ghetto and concentration camp at Terezin when I read this book. Even the way in which Mandel weaves the various threads together doesn’t feel too contrived or coincidental (especially given how few people are left after the Georgian flu). It just works, and it works beautifully.

At the end of the world, what survive? And how? Would we even have any time for such frivolities as art and music? I’ll let Lear himself answer that question:

O, reason not the need! Our basest beggars

Are in the poorest thing superfluous.

Allow not nature more than nature needs,

Man’s life is cheap as beast’s. (2.4.304-307)

One of the best books I’ve read this year.

- NPR interviews Emily St. John Mandel

- New York Times Sunday Book Review of Station Eleven by Sigrid Nunez (I disagree with a lot of the criticism of the book in this review)