Hidden in Plain View: A Secret Story of Quilts and the Underground Railroad by Jacqueline L. Tobin, Raymond G. Dobard

Hidden in Plain View: A Secret Story of Quilts and the Underground Railroad by Jacqueline L. Tobin, Raymond G. Dobard Published by Doubleday Books on January 19, 1999

Genres: History

Pages: 224

Format: Hardcover

Source: Library

Buy on Amazon, Buy on Bookshop

This post contains affiliate links you can use to purchase the book. If you buy the book using that link, I will receive a small commission from the sale.

Goodreads

The fascinating story of a friendship, a lost tradition, and an incredible discovery, revealing how enslaved men and women made encoded quilts and then used them to navigate their escape on the Underground Railroad.

In Hidden in Plain View, historian Jacqueline Tobin and scholar Raymond Dobard offer the first proof that certain quilt patterns, including a prominent one called the Charleston Code, were, in fact, essential tools for escape along the Underground Railroad. In 1993, historian Jacqueline Tobin met African American quilter Ozella Williams amid piles of beautiful handmade quilts in the Old Market Building of Charleston, South Carolina. With the admonition to "write this down," Williams began to describe how slaves made coded quilts and used them to navigate their escape on the Underground Railroad. But just as quickly as she started, Williams stopped, informing Tobin that she would learn the rest when she was "ready." During the three years it took for Williams's narrative to unfold—and as the friendship and trust between the two women grew—Tobin enlisted Raymond Dobard, Ph.D., an art history professor and well-known African American quilter, to help unravel the mystery.

Part adventure and part history, Hidden in Plain View traces the origin of the Charleston Code from Africa to the Carolinas, from the low-country island Gullah peoples to free blacks living in the cities of the North, and shows how three people from completely different backgrounds pieced together one amazing American story.

This book has been on my radar for a while, mainly because many quilters refer to it and ask me if I’ve read it. I decided to read it, even though I had heard rumblings about the lack of evidence for the book’s premise: that quilts served as secret codes for people escaping north to freedom on the Underground Railroad.

It’s one of those stories one wants to be true, and I suspect that’s the case with Jacqueline Tobin, the primary author. There is some basis for using coded language in the form of spirituals. Harriet Tubman, perhaps the most famous conductor on the Underground Railroad, is known to have used two songs as codes, including “Go Down, Moses.” Another popular story is that cornrow hairstyles were used to convey secret messages to enslaved people. According to the Snopes article on this practice, they “found no tangible evidence of slaves in the U.S. actually using cornrows to convey messages. But this doesn’t mean that these stories should be disregarded, or that the practice never existed.” I suggest the same is true of the story Tobin and Dobard tell about quilts serving as coded messages to those escaping slavery.

The first problem is that Tobin seems to have relied on a single person for this story. It beggars belief that no one besides Ozella McDaniel Williams would have told stories about this practice. According to Laurel Horton in her article “Truth and the Quilt Researcher’s Rage: The Roles of Narrative and Belief in the Quilt Code Debate” in Western Folklore, “the eleven patterns named in the Quilt Code are typical of those popular in South Carolina [where Ozella McDaniel Williams lived] in the early twentieth century” (p. 43). However, some of the patterns did not yet exist before the Civil War, while others did not have the names that Ozell McDaniel Williams gave (e.g., the Monkey Wrench) (Horton, 2017). I was also a bit surprised to learn from Horton’s article that block-style quilt patterns were “virtually unknown” in South Carolina until the 1840s, and that it would probably not have been possible for African-American quilters to hide such quilts “in plain view” (p. 43).

As a qualitative researcher myself, I’d be the first to disagree with critiques that dismiss Tobin’s research because she obtained the information she published in this book from a storyteller. However, we can’t take this anecdote, no matter how attractive it is, and extrapolate that quilts served as codes based on one woman’s story, especially since the story is filtered entirely through Tobin—we never really hear much in the way of direct quotes from Williams herself. I am even more skeptical of the book’s claims that some quilt patterns have Masonic connections. I mean, maybe? I don’t know enough to say absolutely not, but it reads sort of like pretty much every other conspiracy theory about Freemasons.

In terms of style, the authors frequently employ questions as a rhetorical device (I also caught some copyediting mistakes). For me, this style undercut the book’s message and made the authors sound unsure of themselves, which I suppose they may have been. There is also quite a bit of repetition, and ideas might have been more tightly organized. The author might repeat biographical details about figures in the book, such as Denmark Vesey. I found myself thinking, “Yes, you already told me that,” a few times as I read.

This story has taken root, and so many people want it to be true that I doubt my critique will amount to much. So why two stars? I found the story compelling, as Horton states in her article as well. I also appreciated the discussion of modern quilters such as Faith Ringgold, Michael Cummings, and Carolyn Mazloomi. I also enjoyed reading about some of the connections between patterns and African art, though I will independently research those claims to verify their accuracy. I probably should give the book fewer stars, but I admit it held my attention. Now I can say I’ve read it when people ask, and I will definitely tell them what I think. In the immortal words of Jake Barnes at the end of The Sun Also Rises, “Isn’t pretty to think so?”

Reference:

World War II Quilts by

World War II Quilts by

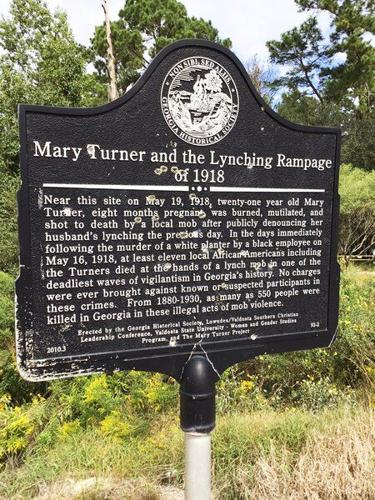

Elegy for Mary Turner: An Illustrated Account of a Lynching by

Elegy for Mary Turner: An Illustrated Account of a Lynching by

The Five: The Untold Lives of the Women Killed by Jack the Ripper by

The Five: The Untold Lives of the Women Killed by Jack the Ripper by  Barracoon: The Story of the Last “Black Cargo” by

Barracoon: The Story of the Last “Black Cargo” by  We Don't Know Ourselves: A Personal History of Modern Ireland by

We Don't Know Ourselves: A Personal History of Modern Ireland by  Crazy Horse and Custer: Born Enemies by

Crazy Horse and Custer: Born Enemies by  Never a Dull Moment: 1971—The Year That Rock Exploded by

Never a Dull Moment: 1971—The Year That Rock Exploded by

Sourdough Culture: A History of Bread Making from Ancient to Modern Bakers by

Sourdough Culture: A History of Bread Making from Ancient to Modern Bakers by

A Short History of Nearly Everything by

A Short History of Nearly Everything by